Alistair Hicks (AH): Using text and images goes back to illustrated manuscripts, when it was common to use images as well as other means of communicating.

Elo-Hanna Seljamaa (EHS): Have you noticed any regional differences in the use of image and text: the cultural space where Marko Mäetamm is coming from and Raymond Pettibon’s use of images and text?

AH: Actually, I think this is very much an international trend and it cuts through the differences but, if you think back to medieval Europe, that was a very international time. It was a time when the Church united everyone, so you had scholars who all communicated in Latin. Today, we are in a time where communication can be international, and the potential is there for us to be able to communicate.

Liina Siib (LS): How long did you work on this project? How did this project come about?

AH: It came about partly through Olga [Temnikova, gallerist, Temnikova & Kasela gallery – Ed]. We met three years ago at the Frieze Art Fair in New York. I led an ad hoc guided tour at the fair for Rein Lang, who was the Estonian Minister of Culture at the time, and introduced him to the works of Raymond Pettibon. Olga later mentioned that Pettibon was Estonian on his mother’s side. I had no idea. Then we decided on the spot that he ought to have a show in Estonia. So I went to check with one of his gallerists, Sadie Coles. I met with Raymond in London and then in New York; he had never been to Estonia. For a long time, I have been interested in his works. The idea of using Marko’s works was almost simultaneous between the Kumu Art Museum and me when we were thinking about who would fill the other half of the exhibition space. It just seemed obvious that Marko was the one that you would show at the same time.

LS: Two different types of anxieties.

AH: Lots of anxieties.

EHS: And anger.

AH: Luckily I am very laid back. Actually Raymond is quite laid back in a way but full of anxiety in another, as you said, and filled with outrage, fighting with the world.

EHS: It seems like he follows the news and everything very closely. He is very much in dialogue with what is going on in the world at large.

AH: I am not quite sure how he assimilates information because he does it very rapidly.

EHS: I translated Raymond’s texts into Estonian for the exhibition. And I actually got to see the texts before I saw the images. It was interesting for me that the texts worked perfectly well without the images: they were very poetic.

AH: Yes. I also like the way he purposely makes mistakes in the texts. Look, he wrote ‘holey’ and then ‘cross fatched image…’.

EHS: Yes, I was reading it in this morning and was glad I did not have to translate that one. While translating the texts of his works, I noticed how they go all over the place; they are very intertextual, referring to literature and all sorts of things.

AH: When we were talking yesterday with Raymond, there was suddenly a reference to Shakespeare. His use of language is quite Elizabethan, and then there is the way he abuses the language. In a way, as you said, it is not preconceived. Language as a source. Not something to be revered. Very practical. His work is uncompromising. That is the difference. Everyone always feels that they make too many compromises.

EHS: If we compare the role of images and text in the works of these two artists, what can we say?

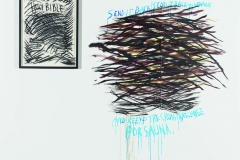

AH: Comparing their use, Raymond made films, quite hard core, a long time ago. From a visual point of view, quite often you feel a lot of Marko’s work is like storyboards, but with Raymond they are more individual, even when there is a sequence. They are more isolated, works on paper. Marko explores lots of different media. Raymond has done a bit with other media but he generally works on paper. The basic use of text and images is so natural to both of them. It is quite similar the way they do handwriting. Marko’s work are more like graphic novels: he uses the comic format more often. That is something that I will think about when I write the book. I don’t think you can attribute the differences to the individuals; there is more about being part of today’s society and responding to it.

EHS: And using English as a new lingua franca. I have the impression that Marko is more in control of his output. In Pettibon’s case, it is more like a flow starts coming or maybe it is coming and you are not quite sure what is coming at that point, when it is coming etc.

AH: Yeah. With him there is no point in organising it anyway because the unpredictable form is enjoyable, quite an old style of artist, sort of a rock star. He is about eight years older than Marko. I suppose their lives are quite different.

LS: Marko’s work seems to contain more of the autobiographical element more explicitly, or rather he exploits it. We don’t know if it is true or not. Everyone believes what they believe.

EHS: Yes this relationship between the autobiographical and fiction, that’s what it is like.

AH: Raymond’s father was a writer and taught at a university. So Raymond was brought up in a literary atmosphere and carries books around with him. Usually he tears them up and takes bits from the books that he wants. That’s the approach: when he does the work, he is just tearing his brain up and placing it on the wall for viewing.

Raymond

AH: Yesterday when he did his last painting on the wall, I did not want to disturb him but we had a conversation while he was painting it. That was fascinating because I felt in a way he was talking to himself as much as talking to me and it was all about the process. To be a painter in a way is quite a lonely existence. He was talking about how everything that he does actually refers to something but then if someone like me goes and hangs it, different references come out. The one thing he did yesterday explains it extremely well: it says ‘I cannot count on a flame of rage.’ In a way, he is an angry man and he expresses lots of thoughts about how the world is so fucked up. Each work is independent but they link up, or a lot of them link up, because it’s him, it’s him painting. And so what makes sense and what doesn’t make sense is just like a human life, isn’t it? A sequence of what he is doing. Now you have to come into the final room, which contains 18 Stalins. Here it feels very much in honour of his uncle (Otto Peters, b 1919) and his time in Siberia, in Stalin’s gulag, where he spent 11 years for fighting against the Russians. Raymond made the series from 1985 to 1987.

LS: It is a great series. Somehow Stalin becomes one of the Party guys he ordered killed in 1937. He looks here like a composite of the communists executed during the purge. It reminds me of the portraits of Mao Zedong as well.

AH: I wanted to put them up as an Army of Stalins marching at you because they are all different sizes. But in the end I thought it was more powerful just to have them so that their eyes are all lined up. Eha Komissarov also did not think it would work as an army so we came up with the idea of lining them up by their eyes. It is interesting if you compare it to images of Mao. Strangely enough, the image of Mao we remember now is by Warhol.

Marko

AH: It is quite nice to have such a contrast. I remember talking to Marko about the idea of Home and Away, the journey home, and what we do with Pettibon that is about his family’s journey away. All his rooms are different rooms. It’s a house but it doesn’t make sense. There are no bedrooms, for instance. But there is a kitchen. And this maze into darkness is very particular. I love mazes and imagine him using all the space to create false trails and going off etc., but instead what happens you know… this is how it ends.

LS: Like a long movie.

EHS: Sort of nauseating in a way.

LS: I think it also explains his work method, where he tries desperately to find solutions to things but ends up with something that there is no way out of.

AH: Marko is just so full of ideas. It just bubbles over. This show is completely full of sex.

Marko Mäetamm (MM): Because without sex we would not be here. It is a very big part of my life. Shit and sex and money: I constantly deal with these things. I am getting older and I think less about sophisticated things. I get tired and work only in one tune and there’s sex.

AH: Would you believe as you walk around this exhibition that he is slowing down?

LS: Not really.

AH: He is still going to the music, running around. This is the video about shooting and the bloody axe coming out. The feeling of horror movies. A sort of haunted house. People found it very difficult to look at, actually.

LS: Five or six years ago Marko would use tiny dolls to present a crime scene and now he has expanded the little figures to life size.

AH: Then there is this positive video with the artist’s wishlist; you sit there and you get this lovely music and no mention of sex. Except, of course, that water is the Freudian symbol for sex. And at the end, beyond the little closet, there is the hidden space, all red, with red carpet and trophies, all with his name on them: a great winner. Every man’s fantasy.

EHS: It’s interesting. You said that the exhibition is like a house but here it is all on the same floor; you yourself have to picture what belongs in the cellar and what goes in the attic.

MM: Say something serious now.

AH: What’s nice for me coming out of this thing is that now I am planning a book about text and image. So it does not feel like the end. I hope to work with Marko and Raymond again. I enjoyed working with the Kumu museum and its team.

EHS: They lived happily ever after.

- Home and Away. Raymond Pettibon: Living the American Dream. Marko Mäetamm: Feel at Home. Kumu Art Museum, 29 May– 13 September 2015; curator: Alistair Hicks.

Alistair Hicks is Art Advisor to Deutsche Bank AG and author of Art Works: British and German Contemporary Art 1960-2000, Merrell Publishers, 2001, The School of London: the resurgence of contemporary painting, Phaidon Press, 1989 and New British Art in the Saatchi Collection, Thames and Hudson Ltd, 1989. In 2015 he curated the exhibition Home and Away at the Kumu Art Museum.

Elo-Hanna Seljamaa (1980), folklorist, PhD, researcher at the Department of Estonian and Comparative Folklore, University of Tartu. Current research interests include ethnicity, nationalism and multiculturalism in post- Soviet Estonia.

Marko Mäetamm (1965), received an MA from the Estonian Academy of Arts. He is a freelance artist, and works with a wide range of media including photography, sculpture, animations, painting and text. He has exhibited internationally and represented Estonia twice, at the 50th Venice Biennial in 2003 and at the 52nd Venice Biennial in 2007. www.maetamm.net

Raymond Pettibon (1957), an American artist known for his comic-like drawings. In addition to his works on paper, he has also made animations from his drawings, live action films from his own scripts, unique artist’s books, fanzines, prints, and large permanent wall drawings.