The two artists with different backgrounds at the exhibition in Kumu Home and Away demonstrate skill in tackling negative social experiences. We would not be able to talk about contextual integrity here if the American Raymond Pettibon with his display Living the American Dream and the Estonian Marko Mäetamm with his project Feel at Home hadn’t created a successful variegated whole. It seems to focus on vague links with the Estonian, which in itself is totally insignificant from the point of view of contemporary art.

Raymond Pettibon (real name Raymond Ginn, b. 1957 Tucson, Arizona) landed at Kumu like a comet. His mother left Estonia during World War II and in the US she became the mother of a five-child, typically American family. The exile-Estonian databases contain no reference to Pettibon. His Estonian roots were discovered by Andreas Trossek, the editor of KUNST.EE (Magazine of Art and Visual Culture in Estonia) in the course of research on the US music scene, which led him to the dramatic story of the Californian punk-band Black Flag. In the 1970s–80s, this band marked the beginning of Raymond Pettibon’s remarkable career as an artist, which eventually took him to the top level of essential US artists. Pettibon’s mythology was shaped by such authorities in the art world as Benjamin H. D. Buchloh, with his essay Raymond Pettibon: Return to Disorder and Disfiguration in 2000 and the curator Okwui Enwezor, who exhibited his work in 2002 at Documenta 11.

The roots of the Estonian artist Marko Mäetamm, b. 1967, lie in Soviet-era Estonian art and traditions, which were not suitable for themes that Mäetamm tackles at the exhibition. Mäetamm was the first Estonian artist who, without being a caricaturist, found a way to black humour and filled the gap caused by the banning of surrealism in Soviet culture. Renato Poggioli describes black humour as a 20th century concept, defined by surrealists: it is pathetic, grotesque and artistic, and is linked with romantic irony and the spleen of decadents, expressing the absurdity, coarseness and paradoxes of modern reality; black humour is often associated with tragedy or equated with tragic farce.1

In 2000 Mäetamm compiled a comic strip-like series of paintings with numerous dialogues, God, the Devil and M. Mäetamm, where God and the Devil chat with Mäetamm about his appearance, behaviour, thoughts and dreams. This marked the beginning of images and plotlines that are part and parcel of Mäetamm’s mature work. In 2007, Mäetamm represented Estonia at the Venice biennial. The hero of his tale is a father figure who dreams of destroying his family, to whom the artist often lends his identity to increase credibility. His ability to stage black comedy attracts attention, as does the topic of domestic violence.

Marko Mäetamm and Raymond Pettibon are literary artists who use text in their work; they share the habit of nihilistic self-determination and reflecting on the aura of crime, which is usually connected with artists working with themes concerning the body, identity, individual security and sexuality. There are also similarities in their approach to freedom; for both, freedom is a condition that haunts them, and they avoid this by means of pathological types, gothic themes and fantastic tales. Freedom in the direction of evil, which Bataille writes about, is certainly productive in Marko Mäetamm’s work. In her article, Katrin Kivimaa raises issues that are often repeated in modern art and culture: what is the relationship between a creative person with a strong desire for autonomy and his family, who require at least some sacrifice of his freedom. She says that when Mäetamm in his animated video chases his wife and children with an axe, the confessional undertone, on the one hand, emphasises the seriousness of the problem but, on the other hand, Mäetamm’s manner of presentation, peppered with black humour, lessens the tension and reduces the problem to an exercise of how to use rough comedy…2

Bataille has presented a hypothesis about the essential connection of literature with evil and about links between writing and guilt, because freedom in the direction of evil requires that we go ‘as far as possible’.3 At least three accusations are made regarding black humour: it is scary, it lacks respect for values and manners of behaviour which guarantee the stability of culture and keep it functioning, and it ridicules such serious subjects as death and suffering, making them frivolous. It is possible via black humour to liberate the self that has been determined by culture and open the way to murky subconscious, metaphysical yearning.

Mäetamm’s tales follow the theme of man’s frustrations and shift the main elements of masculine ideology: strength, hyper-sexuality, suffering because of lack of recognition, etc.

Mäetamm’s tales are characterised by repeated narratives, and a tale’s conceptual narrative is also directed by spatial treatments that use navigation methods typical of computer games.

Mäetamm’s display at Kumu has a fixed beginning and end, an entrance hall and a trophy room, where the head of the family, suffering from a lack of recognition, has amassed a red carpet and various trophies. The exhibition proceeds through a labyrinth, where the system of corridors and passages leads the viewer to diverse views, new perspectives and misleading dead ends. Although the narrative stipulates that the action develops in the home of a middle-class family, several crimes and deviations have been adapted to dollhouses and their interiors. Dollhouses also come from the game culture, but here the games evolve from archaic forms of communication, and dollhouse traditions send intense messages of a secure home. Murders are out of place in a dollhouse, but not cruel, and do not destroy the sentimental and comic initial meaning of the location.

Among the keywords associated with Pettibon’s work, conflict and society matter most.

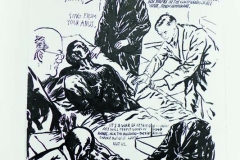

The splitting of his authorial position is expressed in a bright mentality and a dark atavistic side. Pettibon is acclaimed as an artist who has broadened art perspectives, as his novel views on the usage of text influenced the emergence of the second generation of American artists working with text in 1980. This, in turn, is surrounded by his grim reputation as a punk-anarchist. Its inner chemistry is tackled by Benjamin H. D. Buchloh’s analysis: “The harsh and clumsy drawing style of Pettibon’s early zines actually does not allow one to distinguish easily whether these remain deliberately close to the drawing culture of underground magazines as a result of a virtuoso performance of false naiveté, whether drawing skills and artistic knowledge are displaced here by a gesture of solidarity with the compulsive crudeness and the instrumental emergency with which zine drawings are driven to communicate with their marginalized and self-marginalizing audiences, or whether Pettibon’s drawings only acquire their astonishing intensity and art-historical and technical mastery in the course of his subsequent development as an artist, gradually moving away from the aspiration for a direct subcultural communication with the members of his presumed audience of post-Altamont sex-drugs-and-rock-and-roll consumers.”4

Pettibon fills his pictorial surfaces with alternating characters and their inner monologues; life bubbles up and Pettibon’s heroes are full of an inexplicable passion to invade space. His favourites are trains, baseball players, surfers who glide on huge waves, criminals and prostitutes who hatch evil plans, and others. Pettibon is known as an excellent storyteller, and he himself mainly considers the most typical feature of his work to be the literary dimension.

Among space categories, Henri Lefebvre singles out ‘perceived space’, influenced by the register of presentation codes indicating the existential state of the one using the space. This is a space where physical extension conveys the artist’s experiences, and it is no coincidence that Lefebvre used Munch’s The Scream as a prototype of perceived space. The painting vividly shows the anxieties and fears that tormented Munch. One of Pettibon’s key works, Vavoom, continues the theme of The Scream; the word Vavoom does not possess the burden of meaning; it is accompanied by a kind of megaphone which blasts this word in various ways and always in bleak landscapes. Pettibon compares this word with the most powerful, elementary base phenomenon, which was uttered “before the language and Babylon collapsed”.

1. Renato Poggioli. The Theory of the Avant-Garde. Harvard University Press, 1981, p 141.

2. Georges Bataille, Jules Michelet. Vikerkaar No 1–2, 2014, p 112.

3. Katrin Kivimaa. Mõistatades Mäetamme. Vikerkaar No 1–2, 2014, pp 173–175.

4. http://dash.harvard.edu/bitstream/handle/1/3205618/Buchloh_RaymondPettibon.pdf?sequence=2