The exhibition “Romantic and Progressive. Stalinist Impressionism in Painting of the Baltic States in the 1940s−1950s” at the KUMU Art Museum was a rare example of a local exhibition focusing fully on art during the Stalinist period.

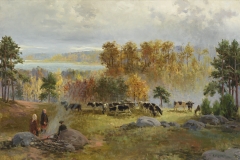

For a viewer expecting cookie-cutter socialist realist thematic paintings and pompous formal portraits of Soviet leaders and Stakhanovite heroes, the exhibition might have seemed puzzling. Although heavy machinery, factories and red flags were clearly present, a considerable portion of the exhibited works consisted of archetypical, seemingly timeless landscapes and genre paintings carried out in Impressionist techniques and colour schemes. Furthermore, the selection of works and the method of display did not directly imply categories of official vs. non-official art or contradictions.

Therefore, one reviewer seemed genuinely amazed that “The exhibition is surprisingly cheerful /—/ all of those [Stalinist themes] are nearly absent. What we see are flowers blooming in vases, artists painting their loved ones, and seemingly free fishermen on seemingly free shores.”[1] When I visited the exhibition, I also overheard some visitors sighing “how pretty!” at the paintings, in sheer wonder.

Turning to the margins of a period that has been subject to large generalisations and at times has been ignored is very commendable but does not come without risks. In a review that included the “Stalinist Impressionism” exhibition, Tanel Rander smartly noted that “matter picked out of history’s trash can /—-/ can only return in a depoliticized and aestheticized form”.[2] The return of ideologically complex art as purely aestheticized visual material is an apt description of the public reception of “Stalinist Impressionism”.

I would like to change perspectives by turning to the historical context and focusing on the genre of landscape painting, which makes up a big part of the artistic production of the Stalinist time in Estonia. One might imagine that Stalinist Impressionism was a local Baltic or Estonian particularity, indicating a distinct continuation of pre-war traditions. But the acceptable stylistic and thematic “repertoire” during the 1940s-1950s in Soviet Russia was not that narrow. Also, the common understanding that landscape painting was marginalised due to the officially imposed hierarchy of genres is too simplistic. In the post-war years, Soviet Russian landscape painting was praised as a means of evoking patriotic sentiments and several artists whose works were driven by a kind of rural nostalgia and impressionist colour scheme were accepted and received high honours, such as the Stalin Prize (for example Arkady Plastov in 1946).

Yet throughout the second half of the 1940s the discourse on landscape painting in the local media, the debate over the “landscape issue”, turned extremely vicious. The appropriateness of works of art and artists was decided in reviews published in the press, and in public and closed discussions that accompanied the exhibitions. Art criticism played a crucial role in arguing for or against the ideological and aesthetic appropriateness of works, but was also required to explain the theoretical notions and provide direct guidance to artists. For nearly every strategy used to secure a safe position, a counterargument fitting the same repertoire of Marxist critique could be easily found to undermine or discredit the artist, and thus the critic. An unsettling example is the exhibition of works by Evald Okas, Richard Sagrits and Richard Uutmaa in 1947, and the accompanying discussions. While the artists were accused of depicting agricultural work methods incorrectly, the critics were blamed for subjecting the artworks to unscientific critiques and not giving clear guidelines. That same year, the Estonian artist and professor at the State Applied Art School Boris Lukats, who was gaining influence in the local art-political scene and was soon to become chairman of the Estonian Artists Union, wrote: “It is remarkable that landscape painting is the domain in which the question of Sovietness and non-Sovietness has been treated in the most questionable way up to this very day. /—/ Just recently, during a public discussion in Tartu, someone proclaimed that nowadays landscape is ‘forbidden'(!).”[3]

Local artists implemented a variety of strategies to meet official demands, such as labelling works with ideologically suitable narrative titles, and adding particular elements, such as pylons, machinery, flags and the colour red. Similarly, art criticism employed discursive strategies mainly to find links with the theoretical notions of socialist realism, connecting it with such local pre-war notions as “closeness to nature” or “national (folk) spirit”.

What created growing turmoil and an increasingly paranoid atmosphere was not the narrow or fixed nature of socialist realism and its demands, but the ambiguity and flux inscribed into the system. According to Jaan Undusk, this ambiguity stemmed from the dialectic contradiction evident even in the core formula “truthful, historically concrete representation of reality in its revolutionary development” and caused socialist realism to function as a mechanism for the reproduction of constant anxiety and fear in the cultural sphere.[4] According to Boris Groys, the contradictory theoretical notions of socialist realism should be linked with dialectic materialism, which means constantly thinking in terms of the unity of contradiction and paradox.[5]

It is important to acknowledge the absence of a rational logic of suitability, especially in the first part of the 1950s and during the purging “campaigns” (a campaign against formalism and impressionism, and a campaign against anti-patriotic bourgeois nationalists in 1949). From time to time, questionable works somehow “slipped through” and it was possible to prop up positions by using official jargon; in other cases, artists were condemned for no evident reason.

The debate over the “landscape issue” indicates regional differences: the fact that genres, themes and strategies accepted in Moscow or Leningrad were problematic in the peripheral Baltics, where the awareness of the recent territorial occupation was acute. Landscape paintings depicting idyllic rural scenery generated such an anxious response in contemporary criticism because they accurately showed pre-war landscapes, covertly and probably unintentionally pointing to the frailty of the Soviet “presence” in the actual “landscape”.

[1] Oll, Sulev. Eesti lill Stalini vaasis. maaleht.ee, 04.02.2016

http://maaleht.delfi.ee/news/lehelood/koik/naitusemulje-eesti-lill-stalini-vaasis?id=73561077

[2] Rander, Tanel Revisionistid ajaloo prügikasti ümber. Sirp, 18.03.2016 http://www.sirp.ee/s1-artiklid/c6-kunst/revisionistid-ajaloo-prugikasti-umber/

[3] Lukats, Boris. Nõukogude maastikumaalist. Sirp ja Vasar 16.08.1947

[4] Undusk, Jaan. Sotsialistliku realismi lenduv reaalsus. Esteetika kui reaalpoliitika riist. – Vikerkaar 2013, no 6 pp 50-53.

[5] Groys, Boris. The Communist Postscript. Verso, 2009 p 36.