The competition for the memorial to the victims of communism is yet another stage in the post-communist rehabilitation pro- cess. Estonian society has been active in this area for about twenty years (the prefix ‘post’ marks a situation where communism belongs to the past, but its shadow is still clearly visible in the present, in memories and habits, and in the environment and political life). Monumental art, which makes it possible to translate meanings, pain, anxiety and suffering into the language of art and architecture, is certainly one of the favourite fields of national self-purging.

There are not too many memorials to the victims of communism in the world. The best known of them is the smallish monument in Washington (2007) – free of artistic ambitions, pregnant with meaning and frequently copied. This monument commemorates people who suffered under the Pol Pot regime, as well as those deported to prison camps from the Baltic countries. Another well-known memo- rial is in Prague (2002), where the victims of communism are depicted as human figures reduced to zombie-like caricatures.

Estonian society has already become rather allergic to monuments with political undertones, especially after the utilitarian glass obelisk with a cross, the Victory monument, which cost 3.5 million euros, was put up on the main square of the capital city in 2009, much against the wishes of the artistic community.

This was not because the topic itself is unimportant and painless. It is instead too difficult to grasp, and the term ‘victims of communism’ was, after all, imported from the Western countries. Estonians were victims of Stalinism, i.e. the deported, forest brothers, imprisoned, murdered, fighters and forced exiles, and they are commemorated all over Estonia; each settlement has its own story. The term ‘victims of communism’ raises questions of who exactly these victims are and whether the distance from the communist past is great enough in the Estonian context, in which the current prime minister and a number of other leading public figures are former communists. Do we have any right and reason to politicise mourning and pain? Why create tensions, instead of trying to get rid of them?

When, in spring 2011, the discussions of the government plan of action reached the memorial to the victims of communism, the representatives of the ministries looked at one another helplessly: who should arrange this and why? The Ministry of Defence, the ‘author’ of the failed glass monument, had no wish to fall on its face again. The brand new Minister of Culture, however, decided to tackle this himself. He was obviously urged on by a desire to prove himself and a genuine passion for various ideological attributes and symbols, whether holocaust or Nazism, and why not communism as well.

It was likely that things would happen as they did in the case of the freedom monu- ment: all attempts to record this abstract ideal would be fruitless. It seems as if the concept of freedom is just too big and too sacred for Estonian monumental art.

The competition was organised hastily, but offered many surprises. Perhaps partly because, during the preparation stage, all organisations representing freedom fight- ers, the deported and the persecuted were ignored. The competition therefore became something like a cool task for art students. Young architects and artists boldly faced the challenge of grasping the ungraspable.

One competition entry explained quite simply: “the monumental form will always be a fascinating genre, but thinking about yet another ideological monument makes people feel sick.” Most of the 66 entries chose a sensi- tively spectacular, depoliticised approach and focused on elegant iconography. Conceptual games were encouraged by the competition conditions, as the task was broad-based and formulated quite loosely on purpose, including the location and cost of the memorial; the contextual and formal interpretation was also not determined and left entirely up to the participants. As there were no restricting factors, fantasy could soar freely.

An expressive and complex-free approach, and aspiring to produce an effect, impression and image formed the centre of most entries. The jury cast aside uncomfortable ‘serious’ solutions. As the aim was not in fact to estab- lish a real winning project, the jury focused on originality, scale and contemporary trends, and enjoyed everything with just as much liberal-mindedness and youthful spirit as the participants.

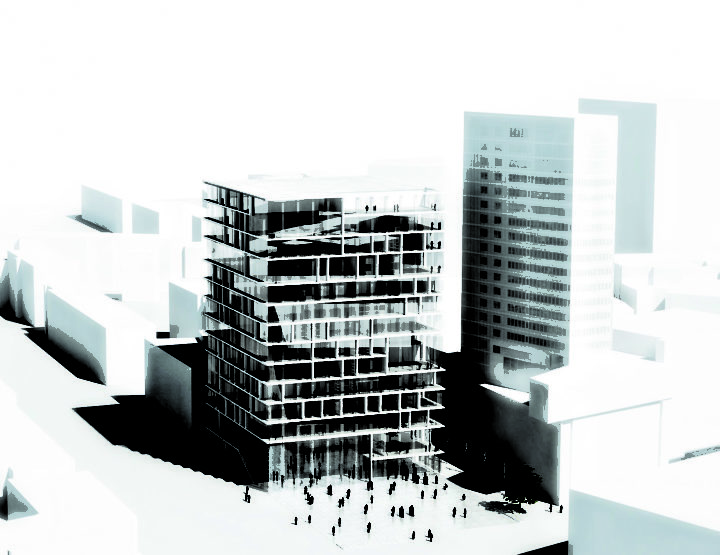

Perhaps for that reason, i.e. being too ‘ordinary’, one of the most impressive pro- jects lacked reckognition: a totally new urban square was created outside the town wall, in the abandoned area between the sea and the Old Town. Its originality was mainly in the sharp light projected from behind, which cast strong shadows. The shadows of people walk- ing on the square blended with hundreds of figures in the pavement: the square was full of shadows … without people.

The effective manifestation of the sense(lessness) of the competition was Ekke Väli’s (one of the few middle-aged partici- pants) work, where a fibreglass copy of a Stalin monument that once stood in Tallinn was put on a pedestal upside down.

Most projects presented various abstract images, all sorts of symbols, where the idea and link with victims of communism, i.e. the context, were not revealed. These could be monuments to whatever. For example, there was the entry that received one of the main awards, which suggested renovating the only existing memorial in Tallinn: the Maarjamäe compact ensemble planned in the 1960s–1980s and never quite finished (Koit Ojaliiv). An additional value here was the grand six-metre wide staircase cut into the klint (this would probably act as a view- ing platform, as for construction reasons it leads nowhere). The crumbling and useless, still-standing abstract complex with modern influences is historically interesting for many reasons. One is that both German soldiers and Red Army fighters were buried there, and were then dug up again, depending on which power happened to reign at the moment. According to more emphatic philosophies, they are all victims of communism, and why not be practical and simply attach another meaning to the existing monument?

As landscape is always potentially more powerful in organising space than is an art- work, many works were set in landscape for conceptual reasons. Manipulating nature, emotions, history and the politics of the moment, and the aspiring for existential or spiritual depth occasionally seemed pretended, although purity, minimalism and the abstract made the competition as a whole a conscious, finely aesthetic act. Relying on the view that the meaning of communism is most lucidly crystallised in Soviet military bases, one com- petition idea was to clear all former military bases in Estonia (altogether about 87 000 ha) of undergrowth and keep them tidy in the future (“Mowing turns wild nature into cultural landscape and military bases into memorials”, according to the author Alvin Järving).

A land-art entry by Armin Valter and Joel Kopli provoked unanimous enthusiasm. It had an excellent location, cleverly linked with a powerful metaphysical experience of space and nature.

Paldiski, a closed garrison town, which the Soviet army left only in 1994, was certainly a symbolic location. Alas, what was called in the project ‘a pure geometrical form’ in the wasteland of the former military campus seems to some more like a ‘hybrid of a silage hole and sewer treatment plant’ (an Internet comment), especially as the authors suggested using old silicate bricks from the demolished collective farm buildings as material. Besides, ‘solemn and awesome’ can in practice be sim- ply appalling, because a 20-metre deep, open cylinder in a place where people hardly ever go, and in which criminal elements are not far away, can spring unpleasant surprises.

There are vague plans to unveil a memorial to the victims of communism on the 100th anniversary of the Republic of Estonia in 2018 (this jubilee promises bigger subsidies from the state). However, the most signifi- cant outcome of the competition is probably its lesson for politicians and ministries. We can be almost entirely certain that the head of government, along with the leading politi- cians who looked through the projects, failed to understand this lesson. This, in fact, serves them right for producing the Victory column of the War of Independence.