The current features of Estonian painting have been shaped by two challenges the experiences of the closed system during the previous few decades, and the stormy renewal of Estonian art in the 1990s.

In the 1970s and 1980s, art in Estonia still basically meant only painting, which acted as a benchmark for all Estonian art. Such a privileged status actually discredited painting in general; already at the end of the 1970s, art critic Evi Pihlak drew attention to the dormant state of Estonian painting in the cultural newspaper Sirp ja Vasar. She asked the question: ėHas Estonian art been completed?‰, referring primarily to the stagnation of painting. Naturally this did not exclude the high standard of various individual artists and the best features of Estonian painting in general. In his article in the almanac Kunst (1993), Boris Bernstein mentions, quoting H.S.Becker, that there is no direct connection between a master‰s ėfreedom‰ and the quality of his art.

During the open 1990s, the need for changes in art strategies became even stronger. The importers of the new art model were the critics who began speaking about painting as an anacronism; a rudiment of the previous system. The tragicomic opposition of critics and painters culminated in the meeting held at the Art Museum of Estonia where the artist Lembit Sarapuu asked point-blank whether he was still allowed to paint or not. The somewhat restrained state of painting lasted until 1995 when it returned to the art scene in the form of an opening exhibition at the newly renovated Tallinn Art Hall. Abstract art dominated from fierce expressionism to minimalism. Abstractionism in Estonia in the 1990s had a perfectly logical explanation art purified itself of the figurativeness normal for the Soviet times.

The 1997 exhibition Confrontations/Agreements became the most extensive display of new paintings. In the introduction of the Estonian Painters‰ Association catalogue published at the same time, Boris Bernstein writes: ėThe self-confirmation of painting in its original sense as a manifestation, a message, and realised in colours on a plane surface is something more than a protective circle of a guild. First of all, it is a sign of the still standing structure of the art world a hint at its organising pole…‰ The concurring theory conference showed that the critics are recovering from the hangover of new medias and that painting has returned to the art scene as a medium to be reckoned with.

The 1997 exhibition mapped the Estonian painting landscape in an archipelagic sense, i.e. grouping the mainstream at the Tallinn Art Hall and, as a contrast, the ėold-fashioned‰ young (students of the Konrad MÉgi Studio in Tartu) at the Rotermann Salt Storage, and around them the deconstructionists of painting and other reform-minding young. Painting ‰98 consisted of four exhibitions with different titles and ideas which took place in five different places: the Rotermann Salt Storage, its Cellar Hall, the Castellan Gallery, Raatus Gallery and Vaal Gallery. The Word of the Painting (conception Harri Liivrand, curators Heie Treier, Juta KivimÉe), The Painter – a Holy Chatterbox. Let‰s Talk about Men (curator Tiina Tammetalu), Painted Reality – Topical Anachronism (curator Kaido Ole), Traditionalists (curator Mai Levin) enabled the artists to demonstrate their preferences. The organisers‰ top priority was to present the works of as many different artists as possible and thus offer a comprehensive overview of the current situation in Estonian painting. Unlike last year‰s practice, no exposition can be regarded as a generational or stylistic ghetto. Generation in the context of Estonian painting no longer means a complex of similar stylistic and ideological features. Thus the satellite exhibition Let‰s Talk About Men which was rather loosely connected with the inner developments of painting, was able to produce unexpected, collage-like cross-sections. At the same time, The Painted Reality Topical Anachronism attempted to present painting as the return of a storyteller and new possibilities at the era of new medias. Curator Kaido Ole had not associated the notion of narrativeness in an iconographic sense with mere reality. Traditionalists at the Raatuse Gallery was put together by artists who thought it necessary to gather under such a slightly provocative motto. The exposition of Let‰s Talk About Men presents a wide choice of works, starting from a feminist commentary to parade portraits by Irene Roos, Einar Vene, Enn Pżldroos, Kaido Ole, Kiwa, Lemming Nagel. The three raster portraits by Kiwa (born in 1972), painted specifically for the Rotermann‰s sterile-tiled cellar, continue the series of autobiographical pop-icons which have characterised his work in recent years. Mari Roosvalt‰s (b. 1945) biomorphic, amoeba-like images have been painted on newspapers. The novel, anonymous aesthetics of monochrome, striped backgrounds is in sharp contrast with the author‰s earlier ėpicturesque‰ arabesques. Irene Roos‰s (b.1972) three large-format portraits, in the style of powerful abstract expressionism, contain figural relicts among other things. The author experiments with a variety of non-conventional materials, typical of the ėgarage-school‰: pink fur, nails, animal bones, silicone paste, tar etc. which form assemblage-like works.

The Vaal Gallery cellar room exhibited a remarkable collection of works by the 1998 graduates of the University of Tartu art department (Evelyn MÄÄrsepp, Priit Pajos, Kaarel Vulla). Differently from the role of the ėold-fashioned young‰ at the 1997 painting exhibition, these Tartu artists now appear in the neo-pop genre. Evelyn MÄÄrsepp‰s (b.1974) series Cure of Disease Under Control uses materials like galvanised iron, enamel and stencil print which mark the bleakness of the hospital environment and shape the mood of alienation. The mood of deconstruction was perhaps most vividly demonstrated in the largest exposition, The Word of Painting at the Rotermann annual exhibition. The exposition presented a wall-to-wall overview of trends, tendencies and orientations, gathering together the figurative, narrative and abstract sides of Estonian painting. In the words of the curator of The Word of Painting, the aim of the exhibition was to justify painting via itself.

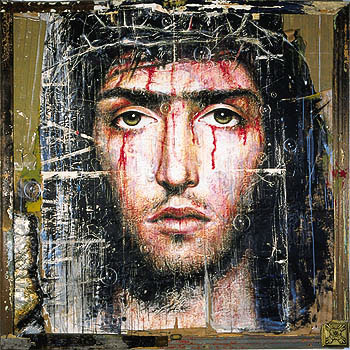

In Alice Kask‰s (b.1976) large-format monochrome, stoical figural paintings elegantly eliminated the problem of colour. On Chessboard exhibited nearby which was painted on wooden boards, she presented a sensitive colour tessellation an unlimited number of combinations as the ABC of painting. Such dismantling of a painting into tiny parts characterised many artists who participated in The Word of Painting. In his Far, Urmas Muru (b.1961) presented an assemblage with plywood grain impressively exposed. Between, on the other hand, had an argument with gravitation red stripes of colour stream from right to left, like ritual murder. The detailed portrait of Christ by Laurentsius (b.1969) dominates not only with its format; but the artist‰s pronouncedly inexpensive ground materials (brown wrapping paper, tape, rough boards), together with his sensitive, elaborate hyperrealism create a strange martyred dissonance. In the conditions of early capitalism in Estonia, this has the effect of a snapshot. JÄri Palm‰s (b.1937) A Building with a Stray Dog presents a portrait of a dog set against the background of the concrete streamline bulk of a building. For years, JÄri Palm has paid special attention to social context and message; this particular work is also a stylistic success there is a synthesis between the realistic left side and the slightly Gerhard-Richteresque right side. Erki Kasemets (b.1961) is a conceptualist with an ideology of recycling whose fragments of painting (samples of style from the glorious history of painting?) and text on various haphazard materials (on this occasion, pieces of milk-carton sized cardboard) are mixed together into large-format rebuses. As an artist for whom painting is merely one way of expressing oneself, besides installation and action-art performances, Kasemets‰s huge collage which functioned in the so-called border situation, no doubt contributed to the widening of the perception of art in the entire exhibition.

Jasper Zoova‰s off-beat Radio 2, a parody of the advertising world but at the same time playing along with its rules was placed dangerously close to JÄri Arrak‰s Bible quotation. This kind of design principle which creates multiple meanings was also evident in the Rotermann cellar exhibition Let‰s Talk About Men and at the Vaal exhibition where Arrak‰s Bible-based work was side by side with MÉetamm‰s anatomically shocking The Birth of the Virgin Mary.

The organising committee accepted several artists‰ wishes to participate in more than one exposition within the annual exhibition, regarding this as a protest against being pigeonholed. The reason why the exhibitions of painting have to be arranged in different locations is primarily the lack of one suitably large exhibition area. Only a number of satellite exhibitions can give an idea of the ever- renewing world of Estonian painting.

The painting exhibitions of the few past years, and the number of young artists who made their debut at the roadshows Speed 1 and Speed 2 (curator Mari Sobolev), have ended the rumours about the isolated state of painting in the ėnew Estonian art model‰.

The fascinating, dynamically developing stylistic and ideological conglomerate of the current Estonian painting allows, in the context of the annual exhibitions, to clearly outline the tendencies and secure the interest of radically different artists and public in the exhibition. Painting ė98 confirmed that Estonian painting has quite flexibly reacted to the challenge of the times.

Johannes Saar

There is not much wrong with Estonian painting at the moment, at least not enough to celebrate this year with the special slogan Painting ė98. The problems are simply old familiar ones that keep bubbling to the surface of the current art world in Estonia. On one hand there are the painters, who more or less fiercely fight for the place they have lost under the sun of fine arts. On the other hand, there are the critics who regard Estonian painting as a stray black sheep who must be handled with parental guidance. Discussions storm more around the art of painting itself, even though nothing much has changed neither in its reception nor in the exhibition halls.

At least people have given up attempts to assemble the whole genre into one huge frame that could be titled ėEstonian Painting‰. The exhibition under discussion is divided in parts; the variegated body of painting has been framed piece by piece into different galleries und subconcepts, so that contrasts, not the consensus, among painters would be more clearly defined. According to Jaan Elken‰s striking metaphor, painting was mapped as an ėarchipelagic landscape‰; a group of islets, between which there may be (or not) accidental traffic and communication. Nevertheless, it seem that this dispersion is rather the problem of curators they stand much further from each other than different faces of painting. Critics are those who overamplify these tiny displacements that have taken place in Estonian painting and talk about the destruction of the art of painting, about restoration, and the comeback of the picturesque. It is a bit too much for Estonian painting to put it frankly: I do not regard these problems as very topical in the local art.

Estonian painting, and more broadly, the whole Estonian culture, is like the only grocer‰s in a village that cannot afford to specialise; for example, only selling salt and pepper or in the cultivation of trans-avantgarde ėbad painting‰. People need everything that is traditionally regarded necessary for life. In 1998 Estonian painting also includes academism, pop-art, trash, conceptualism, naivism, mythologism, abstractionism, expressionism, minimalism and infantile rubbish. Estonian painting must survive much like a well-equipped country shop has to, otherwise people would starve. A manifestion of one single tendency on a grand scale in this colourful general picture, which is now fashionably called pluralism, is impossible. And truly, an archipelago must contain the possibility to sail from an island to another when one gets bored.