In February 2020, a permanent exhibition The Future is in One Hour: Estonian Art in the 1990s, focusing on Estonian art from the last decade of the 20th century, opened at Kumu Art Museum. Until then, the display of Estonian art had covered the period from the beginning of the 18th century until the restoration of Estonian independence in 1991. The new extension to the permanent exhibition explores the proliferation of ideas and dynamic processes of the 1990s, while paying special attention to the role of new media in the art field.

The exhibition is based on the Art Museum of Estonia’s (EKM) contemporary art collection, founded in 1996, when the museum started to purchase installation, photographic and video works from contemporary artists with the support of the Cultural Endowment of Estonia. The 1990s artistic innovations and prolific experimentations with materials and techniques had now found their way into the museum collection, confronting museum professionals with new questions about collecting, preserving and exhibiting. Following the practices customary for more traditional collections (such as painting, sculpture and graphic art) was no longer possible; new principles for collecting, preserving and displaying contemporary art had to be invented. The prevailing topics included the notion of authenticity in reproduced works, documentation of the artist’s intentions and the semantic field of the work, the musealisation of ephemeral works and works that change over time, the long-term preservation of works with a technological component, the identification of associated copyright issues, and others. It took more than a decade to implement procedures and techniques to elaborate these topics and to find possible solutions.1 While the museum was debating questions concerning the collection and preservation policy, new works were being actively acquired at the same time—where the decisions for purchasing contemporary art were mostly directed by the museum’s long-time curator Eha Komissarov.

The discipline of conserving contemporary art has witnessed important advancements in recent decades, and numerous international platforms have been created to provide information on the various strategies and case studies that are leading the way in preserving contemporary art. The earlier purchases to the contemporary art collection of the Art Museum of Estonia have been subsequently reviewed for preservation and display purposes. As the collection

is relatively young, this has been possible in direct dialogue with the artists. In the case of installations, the first version of display is considered of crucial importance—in cooperation with the artists, these first displays have been documented as accurately as possible. The subsequent iterations have also been carefully documented and, when necessary, the instructions for the installation have been updated with the artist. The format of the artist interviews has proven to be utterly meritorious, providing new information about the creation, concept and the artist’s intentions in the work, as well as recording the author’s vision for the preservation of the work. By now more than twenty video interviews, which have also been subsequently transcribed, have been made in collaboration with the Estonian Academy of Arts conservation department and the numbers are constantly growing.

All of the aforementioned activities, which have now been integrated into the daily practices of the contemporary art collection, provide the museum with valuable data that should also be stored with a similar level of conceptual and systematic rigour as the physical or digital elements handed over with the initial acquisition of the work. Therefore, the digital archive where documentation, instructions, schemas, spatial plans, conservation work reports, relevant texts, artist interviews and other materials related to the artwork are preserved, is now considered an integral part of the contemporary art collection. A video installation acquired in the late 1990s, which was at the time handed over on a Betacam cassette accompanied by instructions for display on paper, might by now be followed by a considerable digital “archive folder” without which the re-exhibition of the work might prove to be difficult even after just a few decades.

The recently opened Kumu exhibition about Estonian art in the 1990s is the first permanent exhibition involving media art installations. Authentic and long-term exhibiting of media art created over 20 years ago poses a number of key questions that can be answered based on the materials collected over the years in the archive. The following example illustrates the life cycle of a media installation from acquisition to long- term exposition. An important aspect to understand here is that the essence of the work depends on the specific “behaviour” of digital files. The work described below takes physical form only in the context of an exhibition, and therefore to assess whether the work has been preserved in its integrity, it needs to be installed.

Raoul Kurvitz

Pentatonic Color System

Programme 01, 02 and 03 1994/1999/2020

(EKM 47870 FV 105, acquired in 2000)

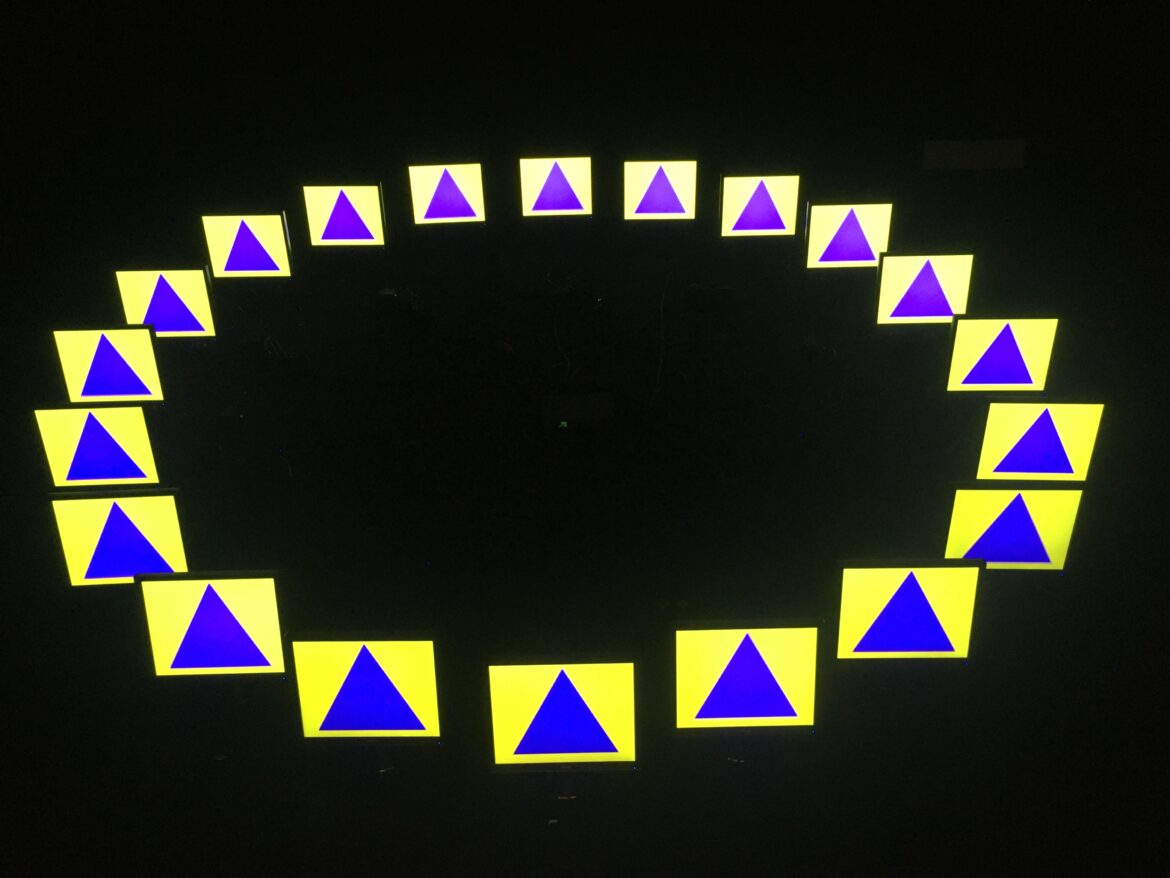

The installation Pentatonic Color System consists of 21 computers and 20 monitors placed in a circle (with a diameter of 3.5 m) on the floor, displaying a series of colour and light effects and images that, combined with quadrophonic sound, create a powerful spatial sensation. The work consists of a cycle of colours and symbols in three parts that blend into optical light. The sound that was specifically created for the occasion is also part of the work.

The original version of the installation was first exhibited as part of Non-existent Art, the 2nd annual exhibition of the Soros Center of Contemporary Art, Estonia (curated by Urmas Muru) in the gallery of the Institute of History in 1994. In 1999, the second version of the work was on display at Raoul Kurvitz’s solo exhibition Symphony in B-flat minor. Post-apocalypse at Tallinn Art Hall. The Art Museum of Estonia acquired the second version of the work from the exhibition at the Tallinn Art Hall.

The main difference between the two versions (1994 and 1999) of the work is that a greater variety of video files was displayed from the monitors in the earlier version, including different forms drawn in Corel Draw by Raoul Kurvitz (circles and spirals; vulva, eye, mouth, fish, knife, moon, triangles, teeth, etc.) and the video files were activated by a synthesizer instead of the computer in the later version. For the 1999 exhibition, it turned out that the part with the forms (part II) could not be activated; therefore, only part I (depicting colour runlets flowing from the heart) and part III (depicting colour charts) were displayed.

In 2000, the museum acquired the later version of the work in two parts on 2 CDs, which included instructions by the programmer and the artist. At the time, the museum did not have the resources to acquire the necessary hardware. In 2008, the work was exhibited for the first time since its acquisition at the exhibition Struggle in the City (Koht, mis paneb liikuma, curated by Maria-Kristiina Soomre and Eha Komissarov) at Kumu. For the exhibition, the necessary computers as well as 4:3 screens, akin to the ones used when the work was first exhibited, were purchased. The selection of equipment was confirmed with the artists and the programmer. A similar set of hardware was used during Raoul Kurvitz’s solo exhibition (curated by Kati Ilves) at Kumu in 2013, when the installation was once more exhibited. Before the exhibition, an interview was organized with Raoul Kurvitz and the programmer Andres Lepp, discussing the possibilities for exhibiting in a situation where due to obsolescence, the technical equipment must be replaced. The installation had been displayed using 4:3 monitors, which are not produced anymore and have been replaced by 16:9 widescreens. When it was incorporated in the new permanent exhibition of Estonian art of the 1990s in early 2020, the previously acquired equipment could no longer be used, as it would not have been able to withstand such long-term use. The museum was able to locate the required number of unused 4:3 monitors, though instead of the previously used cube-shaped CRT monitors they were flat screens. According to the artist, it was important to try to follow the original format of the work, but the sculptural form of the monitors was less significant. Also, the programme running on the computers created using Visual Basic had to be re-written in Linux, as the original operating system (Windows XP) had been retired. The updated programme did not alter the work visually, but rewriting it allowed the restoration of the second part of the original version of the work, which could not be exhibited at Raoul Kurvitz’s solo exhibition in 1999. This opportunity posed a peculiar dilemma for the museum—on the one hand, the museum should strive to exhibit the work as closely as possible to the way it was acquired in the collection in 2000 (i.e. as a programme consisting of two parts, not three, as in the original version of the work). On the other hand, it was hard to resist the opportunity to exhibit the work in its original 1994 version. After some consideration, we opted for the latter, arguing that the reason the second part had not been exhibited since 1994 and was not acquired for the museum collection was clearly technical rather than conceptual. It is important that the choices made regarding the purchase of new hardware, upgrading programmes and the selection of the version to be exhibited were well debated and also documented for future discussions.

This example demonstrates the value of the information contained in the materials that have been collected for the museum’s digital archive. The identity of such complex works exhibited in updated versions due to technological development is mainly preserved in the extensive documentation and accompanying archival materials concerning each case. In order for the ever- extending archive of the contemporary art collection to be used in the future, it is important for it to be systematised, coherent, using unambiguous terminology and precise working procedures. It is also vital to work towards making the database of museum collections3 flexible enough to accommodate different versions of installations and artworks using technological components, documentation describing their essence, detailed instructions, etc. All of these materials are currently stored in the archive of the collection.

1 In 2006, the position of conservator of contemporary art was created within the structure of the Art Museum of Estonia. From 2006 to 2013 Hilkka Hiiop was hired for the position, and in 2012 she also wrote her doctoral thesis about the problematics of preserving contemporary art: Contemporary Art in the Museum: How to Preserve the Ephemeral? The Preservation Strategy and Methods of the Contemporary Art Collection of the Art Museum of Estonia

2 International Network for the Conservation of Contemporary Art—INCCA, Variable Media Initiative, Centre of Expertise in Digital Heritage—Packed, etc. (https://www. incca.org/, https://www.guggenheim.org/ conservation/the-variable-media-initiative https://www.packed.be/en/)

3 The Estonian museums, including the Art Museum of Estonia, use the web-based information system MuIS (www.muis.ee/ en_GB), which is primarily designed for describing and managing physical museum objects and does not provide a convenient management system for museum objects that change in time and are presented in various versions.

- Raoul Kurvitz. Pentatonic Color System. Programme 01, 02, 03. 2nd annual exhibition of the Soros Center of Contemporary Art, Estonia, Non-existent Art, 1994. Photo credit: Õhtuleht, 19. X 1994

- Raoul Kurvitz. Pentatonic Color System. Programme 01 and 03 at the exhibition Symphony in B-flat minor. Post-apocalypse, Tallinn Art Hall, 1999. Photo credit: Archive of the Estonian Artists Association

- Raoul Kurvitz. Pentatonic Color System. Programme 01 and 03 at the exhibition Struggle in the City, Kumu, 2008. Photo credit: Stanislav Stepashko

- Pentatonic Color System. Programme 01, 02, 03. Permanent exhibition The Future is in One Hour: Estonian Art in the 1990s, Kumu, 2020