The 24th February, anniversary of the Republic of Estonia, is our most important national holiday. This year it was a jubilee Ö the 80th anniversary Ö which was nevertheless not celebrated lavishly and triumphantly, but with introverted solemnity. These celebrations were of a young state which had suffered greatly in the past and which had no special traditions, and therefore everybody had to find a meaning for the event for himself. Sometimes this was quite difficult, since our experience is still dominated by complexes stemming from the Soviet period, according to which national holidays with their false solemnity are quite unacceptable.

Several art exhibitions were dedicated to the anniversary Ö in Tallinn, Brussels, Riga. I would here like to introduce the exhibition Freedom of Choice which was held in the Tallinn Art Hall. The curators were Anu Liivak and the undersigned. This exhibition presented a first survey of the more innovative art of the 1990s which had been born together with the new Republic of Estonia, and thus differs from the art of the 1980s and that of the Soviet period.

The most striking difference has naturally been in the techniques employed Ö in addition to traditional painting, graphic art and sculpture, the ‰90s witnessed an explosion of interest in video art, photography, installations and computer art. The exhibition also displayed objects and conceptual jewellery. A further obvious difference is the subject matter of the artists Ö the state, social problems, history.

The art of the national symbols

The key to the exhibition was a series of paintings Blue, Black and White by René Kari (born 1950) Ö three works from the year 1988 which convey the ideal of freedom which arose as a result of the Singing Revolution. They also represent the very last attempt by the Soviet authorities to censor Estonian art. The oil paintings, which depicted the Estonian national flag, were exhibited in March 1988 at the Draakon Gallery in Tallinn for only one day; they were then confiscated, and the artist left a symbolically empty space on the wall where they had been hanging.

Now, 10 years later, when the tricolor is our official national flag, René Kari‰s three forgotten paintings have been brought out again and exhibited alongside other similar works from the year 1997. Looking at the works of Leonhard Lapin (born 1947) and Raul Meel (born 1941), classics of Estonian art, made out of flags with advertising texts written on them, we recognise the materialistic mentality of early capitalism Ö the sacred ideal of freedom is now primarily associated with individual freedom, implying ‹loadsamoneyŠ, profit and entertainment. During these 10 years, ëthe great‰ ideal of freedom has been replaced by a ësmall‰ one.

A change of power is also reflected in the two works by Kreg A-Kristring (b.1962), The Last Standard (1992) and Balance and Antibalance (1992). The first shows Russian roubles with the portrait of Lenin on them; the second shows Estonian kroons as historically new monetary unit.

Art about art

The principle of choosing the exhibits for Freedom of choice was that they had to tackle, either directly or indirectly, but very honestly, our own Estonian problems concerning the economy, politics and the media, and were not to concentrate solely on the games within art, although this was represented too. One of the characteristic phenomena that has emerged in the 1990s is meta-art, i.e. art dealing with art and its surrounding art world. This is, of course, a further development of postmodernist art strategies where all previous art history has been replayed and mixed together. But 1990 meta-art regards past and present art with, as a hidden purpose, the questioning of the quality of observed art, its meaning in society, its change of meaning in time, etc.

One of the most brilliant examples is the installation by photographer Peeter Linnap (b.1960) Estonian Professional Art (1996). It examines the works of well-known local painters and shows a degeneration in ë90s painting as items become objects subject to purchase and sale with no other levels of meaning.

Ekke Väli‰s (b.1952) sculpture Monument to a Monument (bronze, 1990) copies the monument to the Estonian War of Independence, erected in 1927 by Ferdi Sannamees, which was destroyed by the Soviets in the 1940s. Now, in the 1990s, old monuments are being reconstructed all over Estonia and the same process is going on throughout the whole of former East Europe. Ekke Väli is one of the few Estonian sculptors who has dared to interpret an old sculpture in his own way. He presented a pleading boy‰s figure, deprived of both head and arms, resembling an ancient Greek god, using metaphore to refer to the brutality of history.

Looking for the Estonian Monument to Freedom

Constructing a monument to freedom is a topic that has been widely discussed in the press for quite some time. Unlike Latvia, the young Republic of Estonia lacks a monument to freedom which could function both as a symbol and in everyday life, as well as a place where diplomatic ceremonies can take place. At the exhibition Freedom of Choice, Tõnis Vint and Mati Karmin offered two totally opposing visions of the monument of freedom.

Tõnis Vint (born 1942) sees it as a sacred place on Vabaduse väljak (Freedom Square) in Tallinn, together with the Gates of Happiness leading up to Toompea (Cathedral Hill), signifying spiritual serenity and heroic effort. The sculptor Mati Karmin‰s (born 1959) vision is ironic in a good-natured way Ö the freedom monument as a Christmas tree together with a naivistic sun and a cloud. Let us hope that the Republic of Estonia manages to erect a monument to itself while the 20th century is still with us!

Documentary art

In the 1990s, artists have become increasingly interested in historical material associated with particular persons or events. The jewellery artist Urve Küttner (born 1941) has devoted her jewellery series to her teacher Ede Kurrel. She drew from memory, Kurrel‰s ladies handbags and hats and then reproduced them, in tiny delicate filigree silver. Likewise, Mati Karmin (born 1957) has dedicated his documentary installation to his father‰s life. The ëpaintings‰ of Peeter Pere (born 1957) have also documentary background. Instead of a brush, he has used a Soviet stamp, instead of oil paint stamp ink, and the result is a bureaucratic, abstract minimalist painting with an ironic undertone. Kai Kaljo (born 1959) presents a convincingly sincere video monologue dealing with her own life, which reflects the artist‰s position in Eastern Europe. It is simultaneously a conscious self-humiliation because of the canned laughter in the background. Her video Loser (1997) was awarded several international prizes.

A call for reflection

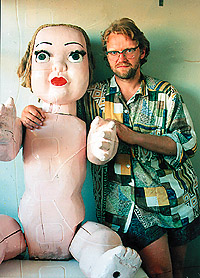

Since the Tallinn Art Hall exhibition raises problems rather than represents the so-called safe art, it should draw attention to several phenomena around us. For example the criteria of values, so forcefully instituted by mass media who bring on stage the antiheroes and proclaim them as heroes. The portraits displayed at the exhibition did not show politicians or respectable cultural figures, but local media stars. Thus Ilmar Kruusamäe (born 1957) has painted the poet and enfant terrible Sven Kivisildnik as a laughing god who looks down upon us from above. And Ly Lestberg (born 1965) contrasts the teacher Linnar Priimägi‰s depravity with the purity and innocence of teenage boys before the World War II. Peeter Allik (born 1966) has depicted the healer Vigala Sass together with an electronic rabbit. On the DeStudio photographic mural paintings we see the Estonian sex symbol Beatrice and the well-known actress Maria Avdjushko as a Madonna. Jaan Toomik (born 1961) draws attention to the alienation of any kind of fanaticism from our surrounding life.

Freedom of Choice is actually an exhibition and a reflection about the situation we have reached; this is not the usual solemn art exhibition which is organised on the occasion of state anniversaries. The exhibition received vastly different responses in artistic circles and in the media, thus allowing the widest possible audiences to discuss it. This was a good result of the exhibition, and one that the curators were silently praying for.