The 800-square-metre great hall at the Kumu Art Museum recently exhibited the work of an artist who has become a fatalist, defining his critical relations with the world from the position of a middleaged man’s fears and anxieties. I have to admit that, via a careful choice of video and video tales, all in harmony with the display of paintings, the viewer was certainly addressed by an expert in existential matters. (1)

Jaan Toomik’s debut in Kumu will probably be best remembered because of his first attempt in film, the 12-minute author’s film Communion (2), which consists of three loosely connected tales. The tales focus on the church, serving God and the relationship between two members of the congregation, a man and a woman. The narrative ranges from satire to sublime poetry. This was an impressively unrealistic story, and I wished to hear the opinions of professionals about Toomik’s film language. Unfortunately I chanced upon someone who was himself just starting to make a film about Toomik and was reluctant to open up to me. In my ignorance, I tend to see Toomik’s film as a video which stretches ambitiously in time and space.

Many critics think that film’s invasion into contemporary art means the triumph of realism in the 21th century. Is it possible that Toomik, well known as an experienced metaphysician and performance artist, suddenly prefers realism?

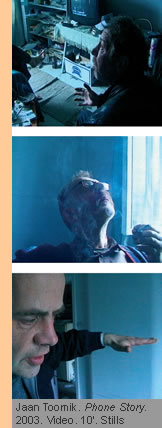

The viewers in Kumu were shown social issues taken from a merciless angle in a cynically realistic manner. For some time now, Toomik has been using near-reality in order to construct provocative and rude narratives, and several of his videos have got stuck in the pitfalls of political correctness. It is quite certain that you will not find at any exhibition the particular video where he introduces the popular habit in post- Soviet prisons of perfecting the penis by embedding tiny pellets in it. (3)

Despite the developments in Toomik’s art, his 1998 video Father and Son still makes the rounds among international curators. It shows the naked Toomik skating and, accompanied by his son’s singing of a hymn, coupling with virgin nature. Seeing that work again in 2006 at the Berlin Biennial at the Jewish School proved that this old video is still a popular example of Estonian art abroad. Toomik has been wise enough not to have added to the sugary interpretation of the family idyll that has brought him fame and, instead of telling fairy tales, he concentrates on psychoanalysis that reveals the truth about the family.

Kumu visitors saw an artist who can, with a clear conscience, be described as depressive, extroverted, megalomaniacal, and tormented by sexual obsessive thoughts. I am not sure what to make of the fact that Toomik quite calmly continues to cultivate a dramatic style of presentation, despite the allergy of today’s experts caused by heroic artists’ positions. Toomik says his latest art project describes the hopes and anxieties of a middle-aged man and, moving around in the exhibition hall among the fantasies about the destruction of his body, we can understand the revulsion that is pushing middle-aged men and women as a subject out of contemporary culture. Toomik’s concept could be seen as a protest against a culture that refuses to accept ageing and death, and this is quite an achievement.

Kumu visitors saw an artist who can, with a clear conscience, be described as depressive, extroverted, megalomaniacal, and tormented by sexual obsessive thoughts. I am not sure what to make of the fact that Toomik quite calmly continues to cultivate a dramatic style of presentation, despite the allergy of today’s experts caused by heroic artists’ positions. Toomik says his latest art project describes the hopes and anxieties of a middle-aged man and, moving around in the exhibition hall among the fantasies about the destruction of his body, we can understand the revulsion that is pushing middle-aged men and women as a subject out of contemporary culture. Toomik’s concept could be seen as a protest against a culture that refuses to accept ageing and death, and this is quite an achievement.

Several peculiarities of Toomik’s manner of depiction are naturally objectionable to many. I have in mind here his hardcore treatment of masculinity, sex and suffering relevant to being a man. In Communion we see a potentially sexist interpretation, where woman is demonised according to typical horror-movie gender constructions. Along with the best sexist traditions of the man-woman opposition, the woman in the film is initially defined as a whore who is happy to be abused, and then the tale focuses on the sexually harassed man. We see a woman who steals the man’s sperm by secretly emptying the contents of his condom into her vagina. A woman’s life, through Toomik’s transgressive point of view, mainly proceeds along the desperately monotonous scale of having or losing a baby.

Together with other ex-Soviet republics, Estonia is a sexually repressed country. The old trends in female underwear clearly show what an insignificant role sex played in the ambitious plans of the empire. In Estonia, anything sexual was further suppressed by the tradition of the prewar Lutheran way of life, which talked about love either in connection with procreation or work. The Estonian culture was well protected from the Western sexual revolution of the 1960s and the impact of the Freud-Lacan tandem; it was denied contact with much of anything associated with sex, and those who picked up this topic in the 1990s were extraordinarily lucky to start from scratch. Estonia’s own traditions also cause a lot of confusion. In Estonia, men are often more vulnerable than women, and the society seriously discusses how the survival of men is totally in the hands of women.

Only in the 2000s can we talk about any serious interest in deconstructing gender roles and an artist or two could leave the impression that the dim sun of the psychoanalytic era is dawning even in Estonia.

However, one must start somewhere, and psychoanalysis, after all, is not a whim of fashion but a serious academic contemporary way of thinking. In the eyes of the Western mainstream, who suggested we change our ever green but outdated surrealism of sexual minorities, realism and social interaction, we are hopelessly lagging behind.

Jaan Toomik is, in a sense, a typical Estonian artist, whose innovative ideas merge with normal conservative attitudes. As a depicter and ideologue of the man-woman opposition, he is in a timeless, non-existent world, where real oppositions can be treated through the prism of some kind of mythology.

In Kumu,  Toomik’s works occasionally seemed like re-writings of Freud. Freud is often criticised because of his asociality and because, in his observations, the world is limited to the sphere of the family. Toomik has his own original vision of asociality, which feeds upon the circumstances of Estonian society and becomes into a treatment of family; he has long since abandoned any critical sense.

Toomik’s works occasionally seemed like re-writings of Freud. Freud is often criticised because of his asociality and because, in his observations, the world is limited to the sphere of the family. Toomik has his own original vision of asociality, which feeds upon the circumstances of Estonian society and becomes into a treatment of family; he has long since abandoned any critical sense.

Toomik’s family model relies on the communal life experience of the risk group consisting of asocial people. Imagine a bohemian problem group leading an asocial way of life somewhere in the depths of a slum. It would be unfair to accuse Toomik of idealising his characters. It is not possible to doubt Toomik’s empathy and, as we can see in his work, the artist is always on the side of his heroes. Toomik’s romantic artist’s position is easy to idealise because most of us would not be able to manage the way he does. From this exotic material, Toomik has produced his very own subject matter, effortlessly latching onto topical themes of social interaction, escapism and emancipation.

Toomik’s videos are family stories in the sense that, although he uses his friends as actors, mercilessly analysing, revealing and occasionally making fools of them, in real life he has been sharing a similar life with them for years. Various videos about Toomik’s asocial friends are based on documentary material. The viewer is astonished to see a gallery of characters who wrestle with existential problems and their tragic circumstances. Toomik has seen plenty, but does not want to be seen as an artist with a strong sense of social criticism. The artist, a visionary and a metaphysician, is more interested in driving out the ordinary that belongs with reality and what is often called a royal voyage towards the unconscious. In the opinion of the supporters of that trend, the unconscious is a mystery, where any chance of genuine reality is excluded. The starting point of Toomik’s videos and paintings is a discovery of the mysterious side of human nature, ie he is trying to uncover secrets. The artist fills the explored topic with allegory and symbolism by simply eliminating fixed, proved phenomena. Add to these manipulations an artist who is able to create strong ima ges and where powerful imagination is not satisfied with simpler procedures, and you take a step closer to understanding Toomik. His own obsessive ideas are best expressed in his longlasting father-and-son saga.

ges and where powerful imagination is not satisfied with simpler procedures, and you take a step closer to understanding Toomik. His own obsessive ideas are best expressed in his longlasting father-and-son saga.

In a mentally disturbed society, we see Toomik in the role of an admonishing and strict father figure, surrounded by mentally retarded sons and daughters. In Toomik’s paintings, the roles change, and every picture could be analysed in the light of an Oedipus complex. Father becomes son, a culprit and a condemned man; the son in turn becomes the judge and so on and so on in endless variations. Toomik has always been fascinated by circulating such values and phenomena, which began with his interest in Buddhist teaching. Toomik paints violent visions of bodily distortions; these are often rough and unreasonable, because too much strength annuls any beauty that might exist. Toomik’s paintings lack a classical quality and misleading ideas about colour, without which painting cannot be imagined. However, the liberation of the body from physical empiricism is more complete and metaphysically attractive in painting than might be imagined.

The fact that, for Jaan Toomik, painting is the kingdom of absolute freedom, which most people seek and think they have found in video or a skilful handling of a camera, is of course a paradox

- Solo exhibition by Jaan Toomik (curated by Hanno Soans) took place in the Great Hall of Kumu Art Museum from 7 March to 20 May 2007. The exhibition was accompanied by retrospective catalogue of Jaan Toomik. Ed

- The film premiered at Kumu auditorium on 7 April 2007. Ed

- Jaan Toomik. Invisible Pearls. 2004. Video. 12’15’’. Ed