The translation of the article was also published in the Eesti Ekspress, 2 October 1998

Even if the changes in life, cultural life included, of post-Soviet Estonia have been radical, there is something that has endured the years of destructions and new beginnings: the Tallinn Print Triennial, with a history of thirty years, was opened for the 11th time. The triennial of this year, however, was also subjected to experiments in renovation. The traditional show, selected by a jury from over 500 applications, was accompanied by several curated shows and satellite events. In the Art Hall, the traditional site for previous triennials, there was a curated exhibition, Tangents, (curator Ando KeskkÄla), and in addition, there were several gallery shows as part of (Reincarnations Book and Reincarnations Paper) or connected to the triennial (e.g. students‰ and children‰s exhibitions). The main exhibition, Touch, took place in the new Rotermanns Salt Storage arts centre.

New feature was the opening up of the show to unlimited international participation. And so the winner of the Grand Prix came from Korea: Chung Sang-Gon won the prize with two large prints combining in a fascinating way (apparently?) handmade paper of very material, tactile quality with the ėvirtual‰ look of manipulated, photo-based digital computer images. Two minor prizes went to Finland and one to Japan.

For me personally it was a lot easier to relate to the ėalternative‰ exhibition in the Art Hall. In fact the new part, intended as a face-lift, made the traditional show look even more traditional not to say outdated. The medium chosen be it print or something else does not make an artist any worse or better. A medium just does not seem to be a sufficient basis for an exhibition. The principle of representation by country is just as bureaucratic as basing the exhibition on a medium.

There were, of course, individual artists and works that were interesting and touching. Looking at the catalogue now after visiting the show, I find myself returning to Guntar Sietins, Tomas Markevicius, Urmas Viik, Liina Siib and Pavel Makov, among others. But apart of the highlights, to be interested in graphic art for the sake of the medium and its inherent features you need to be a passionate expert. I‰m not, and the technical finesses simply get boring to me unless they also have some deeper meaning. For example, in the course of some five or ten years of graphic art in Finland (I‰m not using Finland as a quality standard but simply because I happen to know it best) many print makers have used their medium to investigate, among other things, the functions of the printed image in the past and present, exploring its links to knowledge, imagination and world view, which I find very interesting.

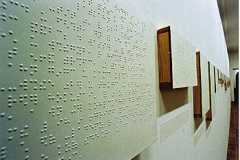

The works in the Art Hall exhibition were supposed to have a connection to the printed image as well. But their approach was very different from the other show. These works are more committed to commenting on the surrounding world and the life of today. Mart Viljus‰s clever shelf of familiar consumer goods with changed names and brands, or Maciej Toporowicz‰s deconstruction of fashion and publicity in the video Obsession are just two examples. My personal favourite, however, was Self-Portrait with Closed Eyes by Juri Albert: verbal descriptions of paintings by van Gogh written in blinds‰ Braille, presented on the wall as paintings. What a dialogue between the limits of the medium (print/painting, image/text) and the limits of the viewer (or reader) and the conditions of communication!

From the point of view of the audience it is easier, in general, to get an insight into a curated show, a whole chosen according to a clear principle. And then, in Tangents, it is no longer a question of the medium. It also has to do with my personal background (I‰m more familiar with this type of language), that the works in Tangents succeeded in conveying meaning, putting a message across in a different way from the ėreal‰ prints. The message of contemporary artists, however, is seldom a pleasant one Teemu MÉki is a case in point in this exhibition but here we must, I think, rather blame the world, not the artists, for being unpleasant.

Ando KeskkÄla explains in the catalogue how print in Estonia was in the old days loaded with meanings of freedom: it was ideologically less controlled than painting and sculpture, and being small and reproducible it was also a means of communication and of spreading information. Similarly, the system of the Baltic triennials was a breaking away from the Soviet cultural hegemony. Today contemporary art in Estonia, it seems to me, is trying delibrately to distance itself from tradition, using it as a foil to create its own profile. Instead of connections with freedom or circulation of information the print in the new part of the 11th triennial was associated with consumerism and the circulation of money. Estonia‰s strong print tradition seems to be losing its power and meaningfulness because it is losing its context.