Interview with Gilles Retsin

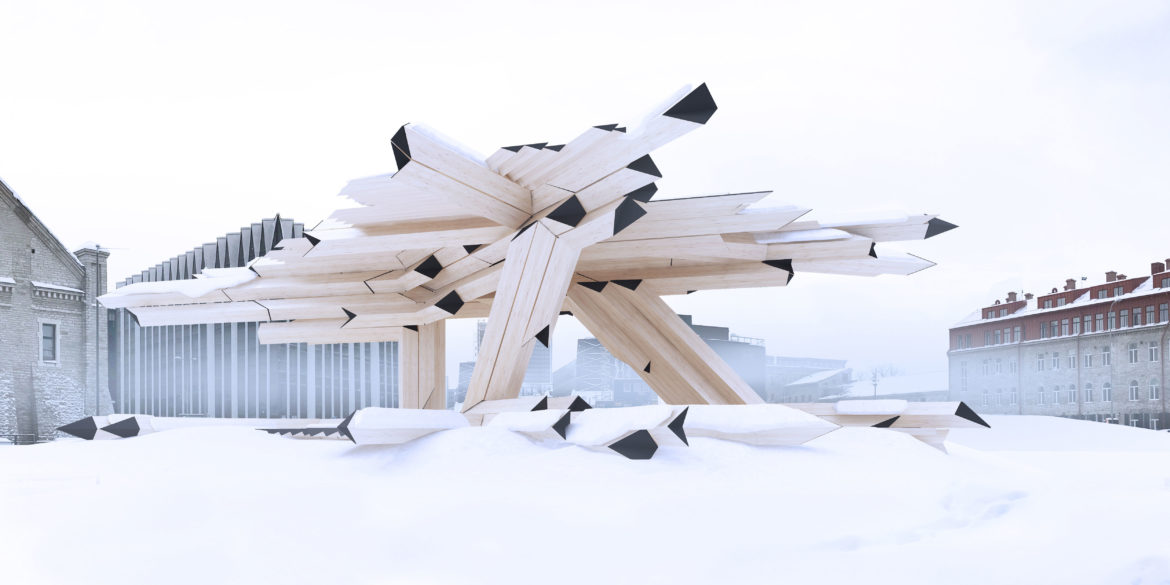

In February, Belgian architect Gilles Retsin won the international TAB Installation Programme open call to build a wooden installation in Tallinn for the architecture biennale in September this year (2017). The winning proposal is characterized by outstanding aesthetic and is intellectually challenging, as it questions current beliefs and trends in architecture, according to jury member Martin Tamke (CITA KADK).

The international open two-stage competition challenged participants to develop creative designs for a temporary outdoor installation, making innovative use of the construction capacities of Estonian wooden house manufacturers. The call raised widespread international interest, 200 portfolios were submitted for the first round from all over the world. 16 architects/teams were selected for the second round by the jury, with final design proposals submitted in February.

The winner Gilles Retsin is the founder of Gilles Retsin Architecture, a young award-winning London based architecture and design practice. The practice has developed numerous provocative proposals for international competitions, and is currently working on a range of projects, among them a 10000 m2 museum in China. Gilles graduated from the Architectural Association in London and prior to founding his own practice he worked in Switzerland as a project architect with Christian Kerez. Alongside his practice, Gilles directs a research cluster at the University College London/the Bartlett school of Architecture, and he is also a senior lecturer at the University of East-London.

The construction of the project will start in August in front of the Estonian Museum of Architecture and it will be opened during the Tallinn Architecture Biennale Opening Week in September.

Triin: What made you decide to participate in the Tallinn competition? There was a lot of interest in the TAB competition, with 200 portfolios submitted in the first round, but what got you on board?

Gilles: I knew Estonia already, because I’d been here to give a lecture at the Estonian Academy of Arts, I already had a personal link with Tallinn. I heard about TAB 2 years ago, knew that the biennale was quite an ambitious project, and a lot of people that I find interesting, like Roland Snooks and Marjan Colletti and Tom Wiscombe were in Tallinn for the 2015 biennale. So I guess that gave me an indication of the ambition. The kind of practice that I’m running – I usually don’t do small pavilion competitions. I mainly either do commissioned projects or large scale competitions. It felt like a good moment for me to do something where I could materialise an idea – and I liked the proposed scale for the pavilion. I ended up turning the idea around though. If you look at my proposal, it’s not really about building a pavilion. It’s a proposal for a way of how to construct. It could be a prototype for a larger construction – I like to say that it’s more a house that I propose, not a pavilion.

Triin: But why turn the idea of a pavilion around?

Gilles: In a sense, my proposal tried to be critical of the idea of a pavilion competition in a sense. Because if you look at pavilion competitions in architecture, they have become kind of a format for experimental architecture that engages with digital technologies. Since 2005 or so, you can see truly thousands of parametric pavilions emerging though formats of workshops or small commissions. The AA had a pavilion programme, there’s so many of them. So it was interesting to me, to think about the format of the pavilion. A whole generation of experimental architects has been doing pavilions upon pavilions, and I’m being very critical of that because it is in the nature of pavilion to be very single-focussed, very narrow. When you design a pavilion, you are basically only talking about material organisation and technology, but it hasn’t been – at least in the last 20 years – a critical device, something that is really connected to real architectural discourse. It’s been more about “look what we can do”. Yes, that was important at one point, but I believe that role of the pavilion has faded now. Now it’s impossible to make a pavilion that still amazes people, because we’ve already seen them for ten years. So I thought: maybe we could do something for Tallinn that is discursive, something that would be more about starting a new era for digital fabrication; less about solely technological innovation and more about housing, politics. It’s not an innocent pavilion any more. And that’s what really inspired me to participate.

Triin: What are you hoping to achieve – what kind of response would you desire for your project?

Gilles: I hope people will notice that it’s not so much a pavilion, but more a building system, a system of production. It’s about digital fabrication methods, not just a device to make something that looks funky, or beautiful, or visible. Digital fabrication has the ability to democratize production. In the previous era of production you needed to own an entire factory, land and capital to produce something – today, you don’t have to any more. You can buy a CNC machine, a 3D printer, put them in your living room. Almost any human being with a little bit of effort can start their own system of production and that is a huge disruption – culturally, politically and sociologically – from previous eras. The technology is driving us to a post-capitalist world, as the figure of the traditional capitalist in the sense of building houses, could disappear. If you want to build a house, all you need is a small machine and timber, the cheapest timber that there is – plywood: normal, off the shelf timber, cheap and thin. Plywood is not usually used for construction. It is mostly used just for decoration or furniture, although there are some examples already, where it’s being tested to build housing. So I’m hoping our Tallinn TAB project would show people how digital production could democratize housing production, how it could help people to construct housing in post-scarcity. You wouldn’t need a lot of people involved in the process any more, or access to factories. We could compare this approach to Corbusier’s Maison Dom-Ino – also a radical, abstract model. If you look at the Dom-Ino skeleton, nobody reads it as a house – it also proposed a new method of production and an aspect of democratization. Dom-Ino was proposed after II World War to quickly house all the people back in Belgium where I come from – to rehouse them fast. Dom-Ino skeletons were be clad in other materials, customizing the design with different facades – that was the original idea, which later disappeared. Our TAB pavilion is in itself quite abstract, but it’s something that desires to be close to the Dom-Ino, it demonstrates a system of production that is radically different from currently dominating modes of construction. It’s new to how people have thought about pavilions before: it’s more about digital fabrication providing social agency, political agency, and also of course architectural aspiration, because it has a very deliberate aesthetical language.

Triin: Where does that leave architects – you say that people could be taking production more into their own hands, not needing the resources they used to. Are you writing the architect out of the process to a degree?

Gilles: I don’t think we are writing the architect out, but we might be writing out the larger scale construction industry. As for architects: what you still need is the knowledge. This is typical for a post-capitalist world – the thing you need is knowledge. It’s not about access to land, labour, capital, but more about knowledge. The architect and the engineer are both knowledge workers. So basically the knowledge that we have as architects and as engineers – that is difficult to democratize – is the ability to design and to make the structures safe and sound and to improve the system. I’m not situating the TAB pavilion in a kind of hippie world of self-build. Also, when I say “democratizing means of production”, I don’t mean people making things in their living rooms per se – I mean more that people could democratically organise production. It could be big scale as well as small scale.

Triin: You say that this pavilion is fundamentally different from generations of parametric pavilions, but how?

Gilles: All the parametric pavilions are essentially always shells. First designers model a form and then use the computer to subdivide the form into segments and then use a machine to manufacture all the different segments and then assemble the segments. Actually, that’s a very non-computational way of working. If you think about how computers work – this is not it at all. That technique is slicing, or segmenting – taking a form and cutting it up. It’s really quite analogue if you think about it, not all that dissimilar to common means of construction. A computer on the other hand is very good at iterating through bits. You give it a 0 or a 1, and then it negotiates and comes up with something. If you look at the meaning of the word “digital” – what it actually means to be digital – it’s about a system where there is a limited set of possibilities, 0 or 1, yes or no. And “analogue” is basically a continuous differentiation of possibilities. So the “accusation” that our pavilion kind of makes, is that none of the parametric pavilions have been doing anything materially with aspects of digitality. They have been rather analogue. There’s a professor at MIT, Neil Gershenfeld who says that if you want to work digitally, then the material that you operate on has to be digital – you cannot operate on analogue material. This is very hardcore of course. When you make a pot out of clay, that’s artisanal, analogue – because that material is continuously different – you can sculpt it into any possible shape. And later on there’s no feedback from the material. Digital material is more like Lego blocks. A Lego block is digital because it has four or six possibilities how you can connect one to another. A Lego block is basically like a pixel, a 0 or a 1. So the idea of the TAB pavilion is that the material that we make it with, is “digital” – it’s basically assembled always out of the same type of piece, there’s no other pieces, like a Lego block, which has a limited, defined number of connecting the pieces. So we’re making a structure that is physically digital. It’s not a segmented whole, instead all the pieces are the same, but you can assemble it to different structures. This pavilion, this building could be a number of different buildings. That’s physical digitality. That might just be one of the first structures in the world that is physically digital. Jose Sanchez and I visited Estonia to give a public lecture at the Estonian Academy of Arts a few months ago. We have worked together for a long time on something in architecture that you call the “discreet”, which started as a criticism towards the previous generations of parametric design. It is about the next generation of young designers working in London, Los Angeles, some in Spain or France, who are really critical of the previous generations. We are asking ‘what were the first parametric designers really about?’ – they had no social agenda, they were experimenting with technologies, but somehow not understanding the true nature of the digital. Instead they were doing mass-customizing, slicing things into parts, so post 2008, the financial crisis we are really trying to reboot the project of the digital, but from a new perspective: a perspective that has a political agenda, that is socially conscious, and that also tries to think more fundamentally about what it actually means to be “digital”, or what it means to work with those technologies.

Triin: How do you think is the timber construction industry going to respond to your proposal? What are the challenges going to be?

Gilles: Well the proposal and the scale of it is very ambitious, so it is going to be challenging. We want to use the thinnest possible plywood and we want to not waste material. One of the most challenging aspects is making it durable in both warm and cold climates, wet and dry conditions, we need to make plywood, an indoor material, waterproof by coating it.

Triin: In that case, why did you decide to use plywood?

Gilles: It’s the cheapest and lightest material to do it. If you’d build it from CLT or something heavier and thicker, you would need heavy industrial machines, making it a different system of construction. Plywood is accessible, cheap, small-scale material, allowing us to build the structure without mechanical lifting. The whole idea is that you take a weak but accessible material, not usually used for something structural, and try to use it for something structural. Of course if you would build a complete municipal housing block, you’d need to change to CLT to make it properly durable.

Triin: You’ve also said that you prefer working with leftover materials, why is that?

Gilles: I prefer working with materials that are accessible, and that are overlooked for construction, but there’s also ecological thought behind the choice of material, yes. But there’s also the aesthetic architectural quality that comes from it.