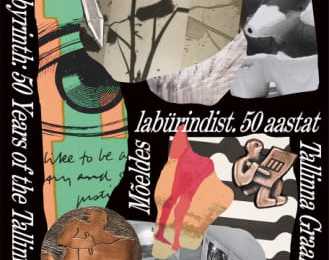

The book dedicated to half a century of the Tallinn Graphic Art Triennials evokes contradictory feelings: the satisfaction that we have managed to continue in the time of independence the tradition of triennials, started in the Soviet period, and made them actually international, as well as the need to admit that the flourishing era of Estonian graphic art has passed (never say forever!) That flourishing time was more or less connected with traditional techniques. It was an axiom in the Soviet Union beginning in the middle of the 1950s (after a number of post-war exhibitions in Moscow) that the graphic art of the Baltic republics, and especially of Estonia, stood out for its technical skill and refinement. The well-known Estonian artist Eduard Wiiralt (1898-1954), a virtuoso in all techniques, was generally considered mainly to be a technical genius. This is misleading. Brilliant technique is always balanced by deeply personal and expressive imagery in his works, especially when they seem to be utterly objective. Personality, personal vision, individual manner and individual treatment of subject have always been the characteristics of a good artist, which is also true in Estonian graphic art.

In the 1920s-30s technical skill was clearly emphasized in the State High School for the Art Industry in Tallinn, most of whose professors had studied in the Central School of Technical Drawing of Baron A. Stieglitz in St. Petersburg. Günther Reindorff (1889-1974), the head of the graphic art department beginning in 1922, deserves special attention among them. He equipped the workshops of the school at such an advanced level that they were still in working order and served the Art Institute during the Soviet period. He was an excellent landscape drawer, but made some perfect prints in linocut, etching and mezzotint as well. Ado Vabbe (1892-1961); who studied in 1911-13 in the school of Anton Azhbè in Munich, was an admirer of Vassili Kandinsky and was the first Estonian avant-garde artist, led the graphic art studio in the Pallas, higher art school in Tartu in 1919-20 and 1930-35. His practical contribution to Estonian graphic art is not large in terms of number of works, but it is significant. In 1919-20 he initiated the printing of the portfolios of expressionist linocuts at Pallas, and in 1946 he made unique colored prints in a technique similar to diatype. Vabbe was especially important as a connoisseur and theoretician of graphic art who instructed several generations of Estonian artists. In 1953-56 he was the director of the experimental studio of graphic art at the Art Foundation in Tallinn. In those days, the studio became the spiritual center of graphic art, and the laboratory of printmaking magicians; with the efficient aid of the master Voldemar Kann (1919-2010), who worked there from 1948 until 1996, leaving the post to his son Uku. The essence of Vabbe’s lessons lay in the correspondence of content and form, expression and technique.

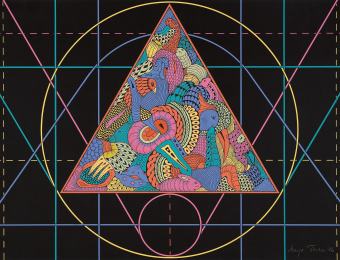

The bequest of the 1920s and 1930s in the techniques of engraving, etching and lithography was sufficiently rich that it served as a reservoir of know-how for Estonian post-war graphic art. There were a number of artists who served as bridges of graphic culture between two eras, and between older and younger generations. Among them, Aino Bach (1901-1980) and Alo Hoidre (1916-1993) were most influential, the former in the sphere of intaglio print, and the latter in the field of lithography. Bach never exhibited at the triennials, but Hoidre was one of the prize winners in 1971. There were talented and innovative middle-aged graphic artists who received triennial awards, including Allex Kütt (1921-1991) and Olev Soans (1925-1995). But it is characteristic of the competitions of that epoch that the artists of the upswing of the 1960s, representing the most vigorously and individually surrealistic and abstract tendencies – the Estonian Peeter Ulas (1934-2008) and the Lithuanian Vytautas Valius (1930-2004) – were the first prize winners in 1968. In the 1970s the radicalism of the end of the 1960s ebbed, not only because of official pressure, but also due to the influence of a new wave of realism. The ascendant national romanticism was one of the reasons, besides their outstanding individuality and mastery, why the Estonian Vive Tolli (1928) and the Lithuanian Petras Repšys won prizes at the next two triennials. The refined modern treatment of traditional subjects made the juries prefer them, for instance, over the primitive Finno-Ugric world of Kaljo Põllu’s (1934-2010) mezzotints.

There has been a great deal of talk about the difficulties of the organization, the interference of authorities and the differences of opinion of the members of the juries. The three republics were, of course, somewhat different in terms of their historical cultural orientation, and in their attitudes concerning national traditions. But it seems, looking back and taking into account all of the circumstances, that the juries were quite fair and the triennials were quite interesting precisely because of the peculiarities of the three participating countries. The limited circle and its particular conservatism distinguished the Tallinn triennial from grand international shows of graphic art, and made it unique. The requirement of three prints gave a better picture of each artist, and stimulated artists to work and to present themselves as well as possible: according to the criteria of those days, of course. The House of Artists was filled by the public because the art had remained fairly close to them.

One cannot restrain the natural process endlessly. The development towards international imagery, problems and techniques progressed little by little in parallel with the society’s desire for independence. The 8th triennial of 1989 was already more international, with participants not only from Russia, but also from Canada, Finland, Poland and Hungary. The Grand Prix was given to Naima Neidre (1943) from Estonia, and three equal prizes went to Ulla Virta (1946, Finland), Ilmars Blumbergs (1943-2016, Latvia) and Rimvydas Kepežinskas (1956, Lithuania). There were 560 works from 169 artists exhibited in the main pavilion of the Estonian Exhibition Center and it was, in spite of the domination of traditional techniques, a show that could be enjoyed nowadays, too. The technological shift in the art of printing became more and more evident in the following triennials.

As for recent triennials, they have been successful thanks to the close cooperation with other print exhibitions and the intelligence of the competent, well-informed and fastidious team. The triennial should be based on the work of such a team in the future, too, if it wishes to continue to be an event in the international printing art life and not just an exhibition of current work in Tallinn. It should be based on the strong local tradition of printing art which – alas! – seems to have rather faded.