Last year marked two decades of the restoration of Estonian independence, and many public speeches, and the media in general, frequently used the metaphor ‘coming of age’. Even President Toomas Hendrik Ilves mentioned this in his New Year’s speech. Now that Estonia has grown up, the President has called for balance, common sense and confidence. The expression ‘coming of age’, however, has another side to it.

It seems that, in the course of becoming an adult state and society, Estonia has proudly abandoned a feature often associated with the teenage years, i.e. idealism. Idealism, the hallmark of Estonia’s 19th century awakening period, the War of Independence and the Singing Revolution, is still respected – and often directly romanticised – in its historical context. Today, on the other hand, it almost seems like something misguided, something containing a kind of immaturity that we like to reproach the Greeks with. ‘Adult Estonia’ has lost its power, and perhaps its ability, to dream.

Estonian people, of course, still have their dreams in 2012. Dreams of a better life, a job, education, happiness and success. Still, these dreams are of mature people, sensible and restrained: they rely on our possibilities and not on our wishes. And even if they are ambitious – such as Prime Minister Ansip’s pre-crisis dream of Estonia ranking among the five wealthiest countries in Europe – their difference from the present circumstances is purely quantitative.

The big social dream at the end of the 1980s of economic autonomy and our own money became known under the apt name IME [Isemajandav Eesti – self-managing Estonia; the idea stipulated that the Estonian economy no longer depended on the Soviet economic system; the abbreviation IME means ‘miracle’ in Estonian – Ed]. As we now know, this was just a start. What followed was even more miraculous than a dream of a self-managing Estonia. It was something that was ungraspable by the mundane imagination. It was a dream that differed from the daily life and could not be expressed in terms of addition or subtraction.

In that sense, today’s Estonia lives in that distant dream, the fulfilment of which twenty years ago required belief in unlimited idealism. Or rather – this dream would never have come true without that kind of unlimited idealism, which made people link hands in a human chain from Tallinn to Vilnius, hoping that this might lead them to freedom. The Baltic Chain and the Night Song Festivals of course did not actually make us free. People standing in the chain or waving flags on the Song Festival Grounds behaved as if they were already free, and thus the 20 August declaration of the Supreme Soviet was merely a stating of a fact.

Strangely enough, twenty years later the situation seems to be a mirror image of the previous one. We are all free, and maybe for that very reason we do not have any special reason to behave as free people. Our freedom is passive, something we know we have, without bothering to think about how precisely it is expressed, what it means or what it requires from us. As adults, we are used to the idea that freedom exists. We feel that people are free in the same way that they are blonde or tall.

Jacques Ranciére once emphasised that politics means expanding borders in the field understood as ‘political’, whereas in recent years in Estonia the ‘political’ field of meaning has been narrowing. When Siim Kallas, Tiit Made and Edgar Savisaar suggested the idea of a self-managing Estonia in 1987, it was certainly a political step. Today, on the other hand, we are told that economics is something outside the political sphere. Moreover, it should not be ‘politicised’ with open debates about today’s situation or future prospects. Calls for clear borders of ‘pure politics’ can be seen in other areas as well, for example in education and art. Teachers and artists have been repeatedly told to keep to their own fields and have been accused of meddling in politics. This has happened a few times, e.g. the production of Unified Estonia [a social-political project of Theatre NO99, which established a fictitious political party, held a convention and was taken for a real political power by many – Ed], or the project of the Golden Soldier [Kristina Norman’s project, see also Estonian Art 1/2009 – Ed]. In cases like these, it is easy to assume that art tackling political topics should also accept the essential functions of politics and offer solutions.

Of course, if art sets itself the task of solving society’s problems, it should not be done in exhibition halls or theatres, but in the parliament. Art should be seen – referring to Jacques Ranciére again – as a form expressing political imagination. This is a viewpoint with a long history in European culture, going back at least to the early 20th century Italian Futurism, and perhaps most evident in the European Situationist movements in the 1960s.

The problem of the fading political imagination, and the subsequent narrowing of ‘political’ borders, is naturally not typical of only Estonia. Instead, the Estonian case stands out because this is not seen as a problem at all. Foreign news about democratic people’s movements in Greece, Spain, Italy, Egypt and the United States evoke suspicion and a sense of superiority here, rather than sympathy or curiosity. It is thus difficult to believe that Guy Debord or Raoul Vaneigem could ever become household names in Estonia.

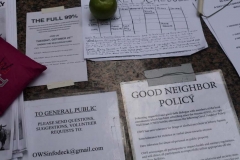

It seems that today’s Estonia has a long way to go to reach a point where movements such as Occupy Wall Street can be seen as political and not just issues of public order. An undertaking such as Let’s Do It!, where volunteers gathered to clean up the country, My Estonia brainstorming sessions or the activities of the New World Society [all civic initiatives – Ed] are not seen today as belonging in the field of politics. In order to change the situation, people must revise their understanding of what ‘political’ actually means. This understanding does not depend on abstract knowledge, but on courage and the ability to dream: the courage and ability not to become and remain adults.

The biggest challenge to Estonian art might well lie here: to give people back their imagination, which we as a society lost when we ‘came of age’.