‘Let them be helpless like children, because weakness is a great thing and strength is nothing. When a man is just born he is weak and flexible, but when he dies he is hard and insensitive. When a tree is growing it is tender and pliant, but when it’s dry and hard it dies. Hardness and strength are death companions. Pliancy and weakness are the expressions of the freshness of being. Because what has hardened will never win.’

While carefully sneaking next to a cracked wall of a concrete ruin, Andrej Tarchovsky’s stalker utters this manifesto of weakness. This insecure guide submits himself unconditionally to the invisible laws of the mysterious Zone. “Weakness is a great thing’”,we both want to persuade you. And yet, “weak” is rarely a positive description. There are kinder words, but it is this and no other which has the capacity to disclose hidden relations, allow for new understandings and open fresh perspectives.

The inventor of the term “weak thought”, or Il pensiero debole, is the Italian philosopher Gianni Vattimo. Even though his writings are from the 1980s, their postmodern message can be extended to our time. Vattimo points out, as do others, that we are living in a world where everything is subject to interpretation, where all values are interchangeable, and even facts are polemic. He proposes the term “weak thought” as a way to exploit this condition of rootlessness in philosophy, as well as in science and art.

The Catalan architect and theoretician Ignasi de Sola Morales was the first to try to appropriate Vattimo’s writings for the discipline of architecture, in his essay entitled simply “Weak Architecture”. Juhani Pallasmaa wrote an essay entitled “Fragile architecture”, based referentially on Vattimo’s essay, 13 years later.

Pallasmaa’s and Morales’ texts can be explained through a metaphor. Imagine a pyramid and a shed as two extremes of a formal spectrum. The pyramid represents man’s ability to organize the chaos of nature by means of abstraction. The countless stone blocks are transformed into the singularity of a mathematical volume. What is appealing to the observer is the monumentality and perfection of the absolute form, which implies that a great power, artistic as well as political, conditioned its creation.

In the shed, on the other hand, we enjoy the exact opposite qualities: complexity and softness, a picturesque disordered silhouette, and organic materiality. Compared to the inceptional singularity of the pyramid, the shed is the result of a long series of accidental decisions that could have come in infinitely varied forms. In this imagined polarity, Pallasmaa takes the position of the shed and proclaims this conquered territory “fragile architecture”. Let’s create beautiful sheds, because the “pyramids” of modernism deprived us of direct sensual experience, he writes.

Morales’ approach is uncanny. He seeks a shed that is as monumental as the pyramid, or rather he claims that the shed can sometimes be a pyramid. According to the Catalan scholar, the experience of multiplicity, which we can relate to the shed, can intensify our already complex reality. This intensification is the new monumentality stolen from the pyramid. This kind of monumentality is, however, rather difficult to define. For this purpose an external party needs to be introduced here. The ruin.

In the realm of things, few are more charged with meaning than the ruin. The bourgeois melancholy of a Sunday walk, millennial tragedies of long forgotten empires, fallen tyrants and tyrants yet to be born are all there. The ruin dissects the world so violently that all of this and more is to be found within. The ruin reveals, hides, confuses and blurs reality so successfully that almost any notion, feeling or lesson can be derived from it.

The ruin is a realm of its own, impossible to grasp in its entirety within the scope of this short article, or in a lifetime, for that matter. It is fantastically and frightfully open, described over and over. Paradoxically, the forgotten creator of every ruin, the architect, rarely showed any interest in this inevitable renegade creation of his own.

I am using the ruin only as an allegory of weakness in architecture. For the bluntest, simplest and obvious characteristics of ruins are similar to some of the most abstract and remote notions of weak architecture. Ruins and Weak Architecture are products of the same conflict between order and disorder, totality and the fragment, the material and the formal. The ruin, in our case, as with any allegory, reveals and illustrates but is also interesting in its own right. It stays within the domain of architecture, which it also illuminates from a remote time.

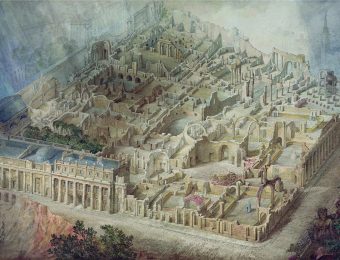

It is usually politicians, not architects, who contemplate the monumentality of ruins. In the crumbling pillars of the Forum Romanum, Adolf Hitler saw a monument of endurance and stability. In front of the ruinous romantic paintings of Herbert Robert, Dennis Diderot questioned the meaning of life. The monumentality of ruins can indeed refer to the history that passed through and between them. The ruin is a screen onto which we project our own images drawn from glorious pasts, real or imagined.

Instead of the antiquarian’s, let us take the architect’s point of view. Without any of the symbolic meaning, reference to heroic deeds and events of past millennia, where in ruins is the monumentality when seen as mere spatial arrangements?

It clearly is not the monumentality of the absolute, that of an obelisk or a pyramid. Often, it is not an issue of scale or dimension either. The central mechanism of monumentality in ruins must lie somewhere else.

The definition of monumentality offered by Morales can hardly be more enigmatic: “a window to a more intense reality”. He also links the “feeling” of monumentality with the simultaneous experience of multiple times. Within the limits of this short excerpt, I can only present one occasion where the ruin offers a literal embodiment of concepts that seem rather distant from reality.

For, in ruins, the past and present, or even multiple pasts, can be seen, touched and bodily experienced instantly and simultaneously. The ruin is a section of time, and as with any section it reveals what was meant to stay within separate domains. Its simultaneity allows for an instant experience of multiplicity that is one of the possible interpretations of the monumentality described by Morales. Simultaneity, quite simply, is the monumentality of ruins.

And it is not just the simultaneity of times. The ruin dissects the world in various ways. The section is its most powerful tool. The suddenly exposed intimacy of a ruined home, for instance, offers us an experience of simultaneity of a rather inappropriate kind. In a terrific passage, the novelist Rose Macaulay describes her own house in London, destroyed during the blitz.

“But often the ruin has put on, in its catastrophic tipsy chaos, a bizarre new charm. What was last week a drab little house has become a steep flight of stairs winding up in the open between gaily-coloured walls, tiled lavatories, interiors bright and intimate like a Dutch picture or a stage set, the stairway climbs up and up, undaunted, to the roofless summit where it meets the sky. The house has put on melodrama, people stop to stare, here is a domestic scene wide open for all to enjoy.”

It is no coincidence that this terrifyingly disective simultaneity has been exploited as a tool of representation of architecture. The painted visualizations of Joseph Gandy imagined designs not yet built as ruins. This technique had the revelatory capacities of the section, while keeping the integrity of the artwork intact.

Similarly, the ruin offers tools for an intensification of architectural experience, of which one can be described as a certain quality of simultaneity. The others, which will not fit within the constraints of this short article, are openness, disorder, fragmentation and uselessness. All of these outline the common ground between the pleasing formal complexity of ruins and certain types of architecture, where the will of the designer and actuality clash in a felicitous manner.

Somewhat paradoxically, it can be said that weak architecture is a product of intensification. The intensity I have in mind is the intensity of feelings encouraged by a crack between two irreconcilable fragments, that of two centuries meeting in a detail, one inspired by an unexpected breach of rhythm or the joyful deprivation of the expected.

Weak architecture is a product of the conflict between the pyramid and the shed, the conflict of two opposing styles or the transitions between them, the project and the site or multiple projects, even the designer and the client. Such projects show all of the scars of the battles from which they emerged. The accidents they suffered from are in striking resonance with the ruin. In fact, it is through the ruin that they can be conceptualized. And it is through the ruin, again, that a more general idea of architecture can be proposed. Architecture that, like the ruin, fuses the disharmony of the eternal human urge for imperfection with the pleasure of form and the beautiful abstraction of the artistic spirit. Architecture which, for its dilatory relationship to the imposing power and singular order, can be called, for instance, weak.

This article is an excerpt of Tadeas Riha’s Graduation Research Thesis for the Faculty of Architecture, at Delft University of Technology, 2015. Tutors: Tom Avermaete, Jorge Alberto Mejía Hernández and Mark Pimlott.