This summer, a year has passed since one of the most high-level architectural competitions in Estonia, but the question of whether the chosen design was the best is still debated. Can the Spanish architects Fuesanta Nieto and Enrique Sobejano and their company actually realise here their idea of an airy pavilion-type building amongst trees, which they presented in their competition project Tabula? The doubters point out the huge cost of the glass building and the later maintenance expenses, all sorts of obstructing regulations, possible damage to the natural environment and many other factors. It would of course be possible to choose other locations and build totally different structures, but the international jury has made its decision on the basis of the works presented at the competition, and the choice was approved by Arvo Pärt personally. It is essential that this building be in Estonia and not anywhere else. The forest of Laulasmaa, with its cultural history, which has inspired so many Estonian composers and musicians (Eller, Tamberg, Kaljuste, Mägi and others) is the best location possible.

We should immediately mention that the jury was unanimous in their decision. This particular work emerged by the end of the second working day of the jury, when too conceptual and architect-centred entries had been discarded. During the competition, I think it was Nora Pärt who best formulated the idea of the centre: “we should find a design where Arvo Pärt’s music dominates, and not an architect’s ego, the idea that inspired him.” The entry called Tabula was closest to that wish. The idea is actually very simple: the building is placed in the middle of the forest. Plenty of glass and inner courtyards guarantee such a strong presence of nature that every slight breeze and the movement of pine needles and moss can be perceived inside the building all through the year. The idea of the building so inspired one jury member, the famous Japanese architect Sou Fujimoto, that he used the same idea in his subsequent competition work: the House of Hungarian Music, and so successfully that he was selected as a member of the three teams who will design it.

A decisive factor in choosing the work was its flexibility, or the potential to develop it further without damaging the original idea. The form of the building can be altered without any losses by specifying the landscape conditions and programme, while still maintaining the context of the location.

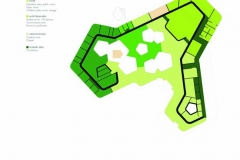

The location is on the edge of Laulasmaa village in a pine forest, on a peninsula close to a limestone slope, where the sea is 1.5 km in every direction as the bird flies. The plot is rather big, but the competition entry placed the building in the upper northern corner, close to the village and the road in order to spare the beautiful nature and landscape as much as possible. All of the rooms are located on one floor under one huge roof, which, thanks to its disruptions (inner courtyards where trees grow), totally disappears into the forest. The inside rooms are surrounded by curvy wooden walls, constituting the rooms of the centre, an archive and a small concert hall. We are in a landscape where the border between the interior and exterior is vague. The forest seems to grow through the house. This sensation is intensified by large glass surfaces and supporting constructions outside that make the building transparent and airy. The only dominant factor is a viewing tower beside the building, and it has more of a symbolic value. A lift takes you up to the viewing platform.

Although much acclaimed throughout the world, the career of the Spanish architects really took off only after winning the Estonian competition. They are at the height of their creative life. This year they were awarded the prestigious Alvar Aalto medal, they also received a high accolade in America – the AIA Honorary Fellowship from the American Institute of Architecture – and their design for the Madinat al-Zahra museum in Spain got to the final round of the Mies van der Rohe European architecture competition. They have won big competitions: a museum and a cultural centre in Munich and Guangzhou, China.

The high level of their architecture was evident this spring at the exhibition at the Museum of Estonian Architecture Window and Mirror. Nieto Sobejano Architects, where models of their work were the focus of the display, and large boards on the walls showed enlarged photographs of architectural details of the same buildings. The bulk of their work is made up of monumental culture-related buildings, such as art centres and museums, mainly commissioned via architectural competitions. During the exhibition at the museum, Enrique Sobejano presented a paper about his work in general and his completed works, and he also talked briefly about the Arvo Pärt Centre. A certain pattern or matrix in details and later enlarged in parts of a building (windows and openings) – in the case of the Pärt Centre, a pentagram – characterises all their designed buildings. Great attention to details which are inseparable from the building as a whole and uncompromising effort regarding the context of the location, as well as form and programme in the designing stage and later at the construction site, have guaranteed them international success. Spatial impressions evoked by their architecture are the result of the carefully considered usage of selected materials and architectural methods. The idea of their most famous, much awarded achievement – the Contemporary Art Centre in Cordoba – relies on hexagonal elements, precisely used as a pattern in the lighting on the facades, windows, light wells and also in the ground plans of the building. These make the monumental concrete architecture light and ethereal.

The Arvo Pärt Centre will be completed in Kellasalu in Laulasmaa in 2018. Hopefully the main idea of the building, transparency and airiness, will not disappear during the process.

This work is difficult to adapt to our harsh northern climate. The architects admitted that this was their first project so far north. The real challenge for the engineers is to keep the architectural idea and still stay within the required energy-efficiency parameters. The trees growing in the inner courtyards have caused a great deal of speculation, and some pines will probably have to be sacrificed. The quite unique, fragile and slowly recovering landscape in Laulasmaa is highly sensitive to any construction work. Builders have to be extremely careful: instead of caterpillar tractors and powerful diggers, spades must probably be used. Considering the architects’ keenness for details, these must be realised with the precision of a watchmaker. The externally simple building will require great effort and care in the subsequent design process and in the construction itself.

No competition design has ever been one hundred per cent realised. It will be quite interesting to see what the building will be like in local conditions, to what extent the Spanish architects can translate their idea into the local environment. They must take into consideration the highly volatile climate and the client’s low financial capacity, i.e be prepared for compromises. Good buildings are finally completed through a process in which all participants are equally involved and at the same time ready to take risks and go beyond established limits.